USMC

USMC

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

PCN 143 000177 00

MCWP 3-03

U.S. Marine Corps

Stability Operations

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

Headquarters United States Marine Corps

Washington, D.C. 20350-3000

4 April 2018

CHANGE 1 to MCWP 3-03

Stability Operations

1. This publication has been edited to ensure gender neutrality of all applicable and appropriate

terms, except those terms governed by higher authority. No other content has been affected.

2. File this transmittal sheet in the front of this publication.

Reviewed and approved this date.

BY DIRECTION OF THE COMMANDANT OF THE MARINE CORPS

ROBERT S. WALSH

Lieutenant General, U.S. Marine Corps

Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration

Publication Control Numbers:

Publication: 143 000177 00

Change: 143 000177 01

DEPARTMENT OF THE NAVY

Headquarters United States Marine Corps

Washington, D.C. 20350-3000

16 December 2016

FOREWORD

The Marine Corps will continue, with increasing frequency, to conduct activities in support of

stability operations. These operations will span the range of military operations, from peacetime

engagement, to limited contingencies and crisis response, to major operations and campaigns.

During periods of relative calm, combatant commanders will use Marine Corps operating forces,

either Marine air-ground task forces or other task-organized force packages, in support of our

national strategy of engagement. This aspect of our national strategy assists in building host nation

capacities, promotes democracy and the rule of law, and builds understanding of our cultures.

Beyond peacetime engagement, Marine Corps operating forces will participate in both limited

contingency and crisis response stability operations. The expeditionary nature of the Marine

Corps and its role as the nation’s force-in-readiness demands Marines prepare to conduct stability

operations of short or long duration. Participants working with Marines will come from many

organizations such as host nation personnel, various United States Government agencies,

multinational forces, nongovernmental organizations, and private volunteer organizations.

Marine Corps Warfighting Publication 3-03, Stability Operations, codifies tasks, planning

considerations, and other considerations for use by the Marine air-ground task force in stability

operations. It is a result of lessons learned through the development of the joint irregular warfare

capability based assessment and responds to the Department of Defense directive that distinguishes

irregular warfare from traditional warfare. Stability operations are one of a variety of steady-state

and surge Department of Defense irregular warfare and small wars activities and operations.

Reviewed and approved this date.

BY DIRECTION OF THE COMMANDANT OF THE MARINE CORPS

ROBERT S. WALSH

Lieutenant General, U.S. Marine Corps

Deputy Commandant for Combat Development and Integration

Publication Control Number: 143 000177 00

DISTRIBUTION STATEMENT A: Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

ii

Table of Contents

Chapter 1. Overview

Fundamentals..............................................................................................................................................1-1

Stability Operations as a Core US Military Mission ..................................................................................1-3

Stability Operations Response Actions ......................................................................................................1-4

Providing Initial Response ...................................................................................................................1-4

Effecting Transformation.....................................................................................................................1-4

Fostering Stability ................................................................................................................................1-4

Marine Corps Approach to Stability Operations ........................................................................................1-5

Etymology............................................................................................................................................1-5

Aspects of Stability Operations............................................................................................................1-6

MAGTF Execution of Stability Operations .........................................................................................1-6

Stability Operations Tenets.........................................................................................................................1-7

Stability Operations Criteria.......................................................................................................................1-8

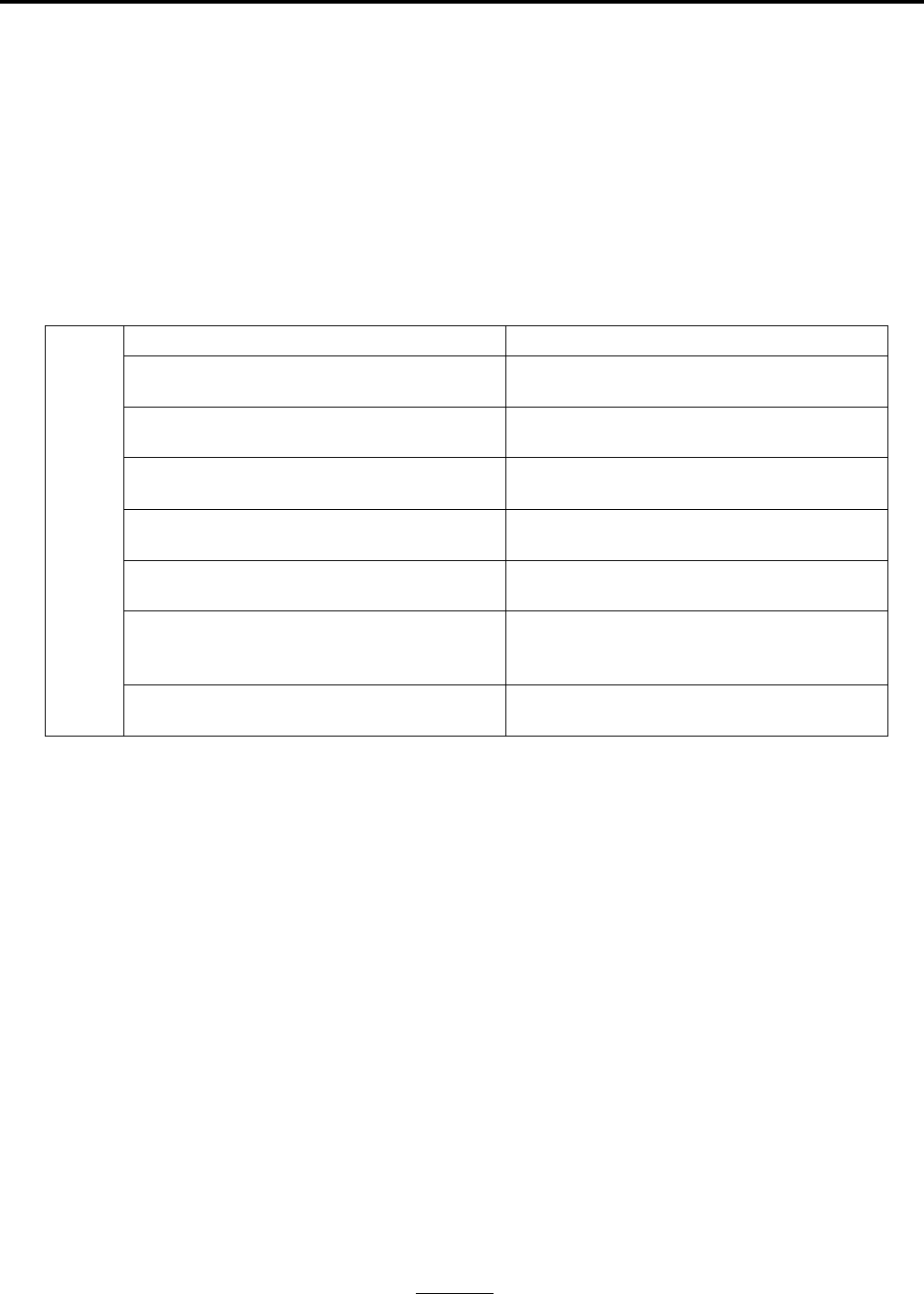

Chapter 2. Functions and Tasks

Functions.....................................................................................................................................................2-1

Tasks...........................................................................................................................................................2-2

Establish Civil Security........................................................................................................................2-3

Provide Humanitarian Assistance ........................................................................................................2-5

Support and/or Provide Restoration of Essential Services...................................................................2-6

Support Establishment of Civil Control...............................................................................................2-6

Support Economic and Infrastructure Development............................................................................2-8

Support to Governance.......................................................................................................................2-10

Chapter 3. Planning for Stability Operations

Unified Action ............................................................................................................................................3-1

Civil-Military Operations ...........................................................................................................................3-2

Integration of Information and Communication.........................................................................................3-3

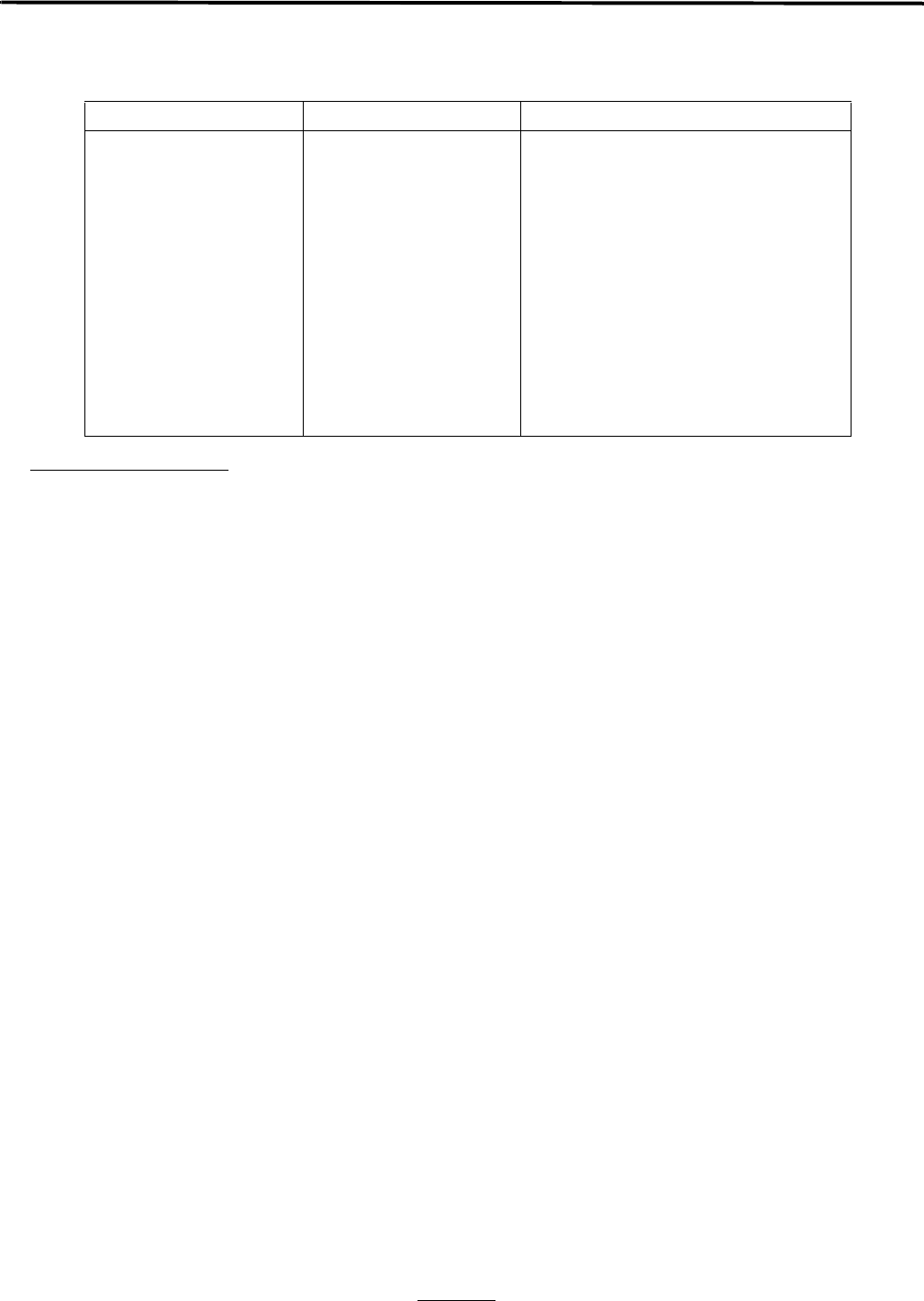

Assessment .................................................................................................................................................3-3

Initial Assessment ................................................................................................................................3-4

Operational Assessment .......................................................................................................................3-4

Assessment Frameworks and Models ..................................................................................................3-4

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

iii

Transitions ..................................................................................................................................................3-7

Funding Stability Operations......................................................................................................................3-8

Legitimacy ..................................................................................................................................................3-8

Restraint......................................................................................................................................................3-9

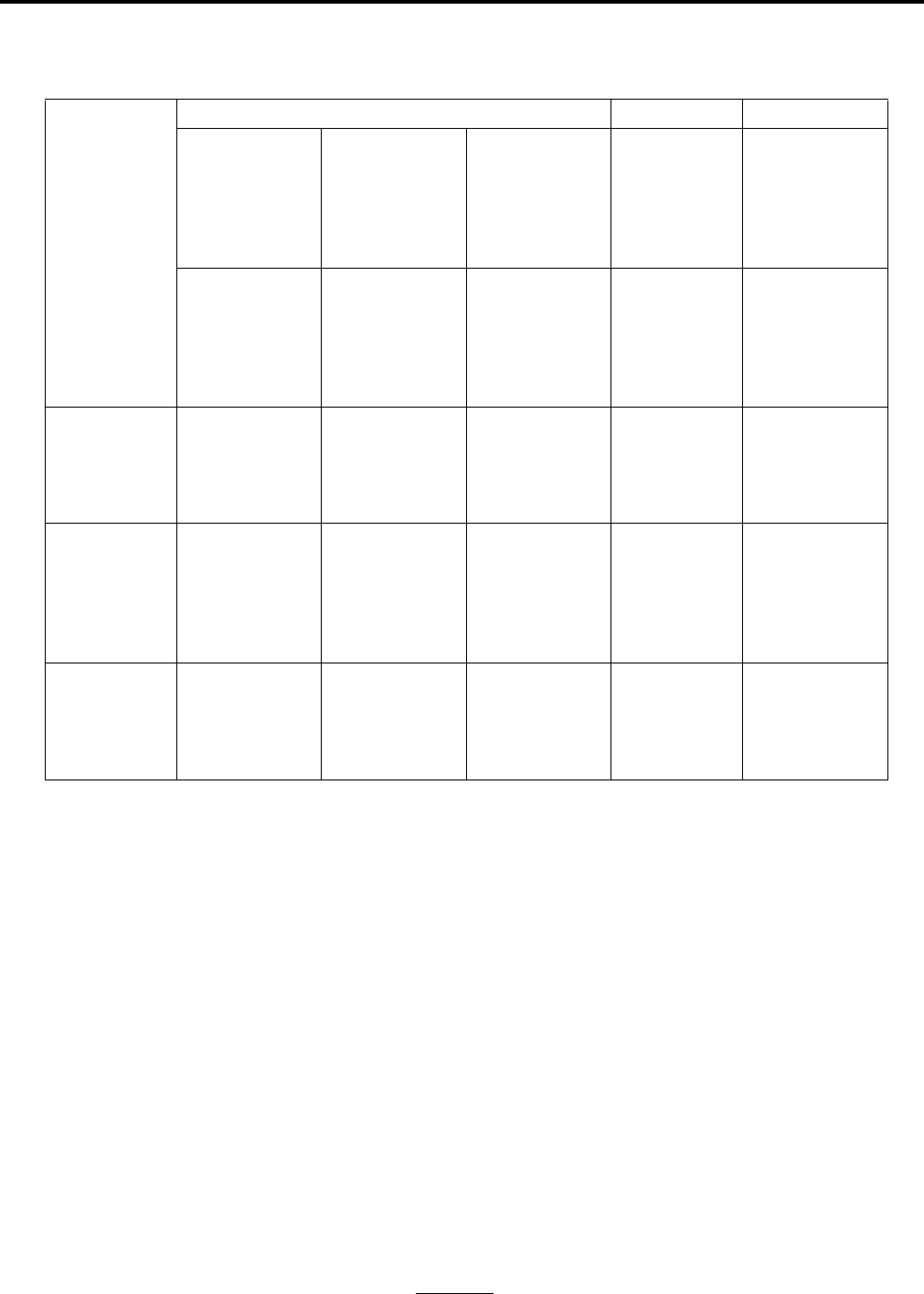

Chapter 4. Maritime Stability Operations

Understanding Maritime Stability Operations............................................................................................4-1

Maritime Stability Operations: A Legal Understanding.............................................................................4-3

United States Code .....................................................................................................................................4-3

Sources of Instability in the Maritime Environment ..................................................................................4-4

Traditional State Challenges ................................................................................................................4-4

Terrorist Challenges.............................................................................................................................4-4

Transnational Crime and Piracy Challenges........................................................................................4-5

Natural Disasters ..................................................................................................................................4-5

Environmental Destruction ..................................................................................................................4-6

Illegal Seaborne Migration...................................................................................................................4-6

The United States Naval Service ................................................................................................................4-6

Maritime, Stability-Related Tasks..............................................................................................................4-7

Aid to Distressed Mariners Operations ................................................................................................4-7

Antipiracy Operations ..........................................................................................................................4-7

Arms Control........................................................................................................................................4-8

Counter Illicit Trafficking (Drugs, Weapons of Mass Destruction, Humans).....................................4-8

Counterpiracy.......................................................................................................................................4-8

Emergency Repair of Maritime Infrastructure.....................................................................................4-8

Exclusion Zone Enforcement...............................................................................................................4-8

Expeditionary Diving and Salvage.......................................................................................................4-9

Explosive Ordnance Disposal ..............................................................................................................4-9

Freedom of Navigation and Overflight Operations .............................................................................4-9

Gas-Oil Platform ..................................................................................................................................4-9

Maritime Counterterrorism ..................................................................................................................4-9

Maritime Interception...........................................................................................................................4-9

Mine Countermeasures.........................................................................................................................4-9

Offshore Resource Protection ............................................................................................................4-10

Port Security.......................................................................................................................................4-10

Show of Force ....................................................................................................................................4-10

Vessel Escort......................................................................................................................................4-10

Visit, Board, Search, and Seizure.............................................................................................

..........4-11

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

iv

Appendices

A Strategic-Level Guidance and Policy............................................................................................. A-1

B Stability Assessment Framework ................................................................................................... B-1

Glossary

References and Related Publications

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-1

CHAPTER 1

OVERVIEW

FUNDAMENTALS

In 2005, Department of Defense Directive (DODD) 3000.05, Military Support for Stability,

Security, Transition, and Reconstruction Operations, established stability operations as a core

US military mission and directed the US forces to prepare to conduct these types of operations

with a level of proficiency equivalent to combat operations. In 2009, the directive was revised and

re-issued as Department of Defense Instruction (DODI) 3000.05, Stability Operations. This

instruction directed the Department of Defense (DOD) to be prepared to—

“Conduct stability operations activities throughout all phases of conflict and across the range

of military operations, including in combat and non-combat environments. The magnitude

of stability operations missions may range from small-scale, short-duration to large-scale,

long-duration.”

“Support stability operations activities led by other [United States Government (USG)]

departments or agencies . . . , foreign governments and security forces, international

governmental organizations, or when otherwise directed.”

“Lead stability operations activities to establish civil security and civil control, restore essential

services, repair and protect critical infrastructure, and deliver humanitarian assistance [HA] until

such time as it is feasible to transition lead responsibility to other [USG] agencies, foreign

governments and security forces, or international governmental organizations . . . .”

Stability operations are presently defined as “an overarching term encompassing various military

missions, tasks, and activities conducted outside the continental United States [OCONUS] in

coordination with other instruments of national power to maintain or re-establish a safe and secure

environment, provide essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction,

and humanitarian relief” (Joint Publication [JP] 1-02, Department of Defense Dictionary of

Military and Associated Terms). Stability operations capitalize on coordination, cooperation, and

integration among military and nonmilitary organizations. These complementary civil-military

efforts aim to strengthen legitimate governance, restore or maintain the rule of law, support

economic and infrastructure development, and foster a sense of national unity that enable the host

government to assume responsibility for civil administration. See appendix A for more

information on guidance and policy at the strategic level.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-2

Several aspects of stability operations deserve emphasis and explanation:

Stability operations are an overarching term. Stability operations include many subordinate

missions, tasks, and activities. Stability-related activities include broad functions, such as

support to governance and stabilization, economic development, rule of law, civil security,

and foreign humanitarian assistance (FHA).

Stability operations encompass various actions conducted outside of the continental United

States. The underlying premise of stability operations is that a stable world presents fewer

threats when compared to a world with pockets of instability. The aim of stability operations

is to remove the underlying source of instability and create opportunities for a safer and more

secure environment. While the focus of stability operations is OCONUS, these operations

often contribute indirectly to the defense and security of the United States.

Stability operations are conducted in coordination with other instruments of national power.

Whole of government approaches (i.e., all pertinent USG departments and agencies) are

required in stability operations. Stability operations conducted in countries

with an US ambassador are conducted with ambassadorial (or deputy chief of mission)

coordination and approval. These various missions, tasks, and activities may involve

participation from a large number of USG departments and agencies, intergovernmental

organizations (IGOs), nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), other nations, US

ambassadors, and multinational forces.

Stability operations are conducted to maintain or to re-establish a safe and secure environment

and provide essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and

humanitarian relief. This important dimension of stability operations acknowledges support to

maintain stability in some situations, while in others, to re-establish stability. Stability operations

align efforts to provide essential government services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction,

and humanitarian relief making them preventive, as well as responsive, to instability.

The term “stability operation” can be used in three different contexts. The term may refer to phase

four of the joint campaign construct: stabilize. The term may be used to describe a joint operation

or major campaign. The term may also be used to describe a series of activities conducted

simultaneously with other types of operations as described in, Irregular Warfare (IW), which

states that DOD stability operations may be included as one of a “variety of steady-state and surge

DOD activities and operations . . . that, in the context of IW [irregular warfare], involve

establishing or re-establishing order in a fragile state.”

In general, a military operation is a set of actions intended to accomplish a task or mission.

Although the US military is organized, trained, and equipped for sustained, large-scale combat

anywhere in the world, the capabilities to conduct these operations also enable a wide variety of

other operations. Examples of military operations to achieve stability include, but are not limited

to, civil support; FHA; recovery; noncombatant evacuation operations; peace operations;

countering weapons of mass destruction; chemical, biological, radiological, and nuclear

consequence management; foreign internal defense; counterdrug operations; combating terrorism;

counterinsurgency (COIN); maritime interception operations; and security force assistance.

While stability operations are often considered in terms of actions ashore, they have a maritime

application as well. The maritime domain, which includes both the landward and seaward portions

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-3

of the littorals, connects the nations of the world by carrying 90 percent of the world’s trade and

two thirds of its petroleum. The maritime domain is the lifeline of the modern global economy,

which relies on free transit through increasingly urbanized littoral regions. Marine Corps forces

have an important and enduring role in the conduct of stability operations in the littorals. Often

task-organized with US Navy and US Coast Guard forces, Marine Corps forces perform a variety

of missions associated with stability operations in the landward and seaward portions of the

maritime domain.

Most operational environments require the commander to conduct a variety of operations

simultaneously and sequentially. This is particularly evident in a campaign or operation where

combat occurs during several phases and stability operations may occur throughout the campaign

or operation. Commanders strive to apply the many dimensions of military power simultaneously

across the depth, breadth, and height of the operational area.

STABILITY OPERATIONS AS A CORE US MILITARY MISSION

As a core US military mission, vice a lesser included mission of combat operations, stability

operations require Marine Corps operating forces to be organized and equipped to achieve a

level of proficiency that is equal to that of combat operations. In order to achieve that level of

proficiency, new capabilities may be required and the existing capacity for stability operations

may need to be increased. Stability operations may require innovative organizational approaches,

additional equipment sets, and revised training and educational programs. Marine Corps forces

will need to tailor force packages for greater synergy, while improving capabilities and increasing

capacity to support civil security and control, restore or provide essential services, repair critical

infrastructure, and provide humanitarian assistance.

The six phases of a joint campaign—shape the environment, deter the enemy, seize the initiative,

dominate the enemy, stabilize the environment, and enable civil authority—have stability

operations implications that are integral to the campaign. For example, lethal actions may

facilitate operations in the seize the initiative and dominate the enemy phases but create

insurmountable challenges for establishing stability in the enable civil authority phase. Planning and

executing both combat and stability operations as part of a joint campaign helps create conditions

necessary to enable civil authority, thus speeding the transition process. The significance of this

campaign phasing construct is that it describes the applicability of military capabilities more

broadly than simply defeating an adversary’s military forces. It gives greater visibility to

sustaining continuous forward operations, working with numerous and diverse partner

organizations, responding quickly to a variety of emergencies, conducting wide ranging and often

simultaneous activities, effectively dealing with changing operational situations, and quickly

transitioning from one mission to the next.

Stability operations can occur across the range of military operations and may include both

combat and noncombat activities. Both the Guidance for Employment of the Force and Joint

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-4

Strategic Capabilities Plan direct the geographic combatant commanders (GCC) to include

stability operations as part of the theater campaign plan. Security force assistance, security

cooperation, and FHA are examples of noncombat stability activities that reinforce the strategic

principle that preventing conflict is as important as prevailing in combat.

STABILITY OPERATIONS RESPONSE ACTIONS

Stability operations have occurred with increasing frequency during the past 20 years in such

places as Bosnia, Kosovo, Iraq, Somalia, the Philippines, Haiti, and Afghanistan as well as on

the high seas in places like the Gulf of Aden, Arabian Sea, Adriatic Sea, and Caribbean Sea. As

these examples illustrate, stability operations are not limited to post-conflict applications and may

occur across the range of military operations. Stability operations response actions include

providing initial response, effecting transformation, and fostering stability activities. Depending on

the host nation (HN) stability situation, response actions may occur sequentially or individually.

Providing Initial Response

Initial response encompasses those tasks required to stabilize the operational environment in a

crisis. The initial response normally occurs during or directly after a conflict or crisis and the tasks

are aimed at providing a safe, secure environment and attending to the immediate essential service

needs of the local population. As the crisis evolves, the response force may transition focus to

transformational activities and activities that foster sustainability in an attempt to avert future

crises. The decision for the response force to continue efforts to alleviate underlying causes of

the crisis is political and will vary with the circumstances. As an expeditionary force in readiness,

the Marine Corps plans, trains, mans, and equips itself for crises response/limited contingency

operations. Its focus is on arrival, initial response, stabilization, and transition to follow-on forces.

The duration of the initial response phase can vary. It may be relatively brief, such as following a

natural disaster, or longer, such as following major conventional combat.

Effecting Transformation

Transformation represents a broad range of reconstruction, stabilization, and capacity-building

activities. It may or may not be associated with post-conflict operations and may occur in either

failed or failing states. The objective during transformation is to develop and build enduring

capability and capacity in the HN government and security forces. As civil security improves,

the focus expands to include development of legitimate governance, provision of essential

services, and stimulation of economic development. Concurrently, and as a result of the

expanded focus, stability force relationships develop and strengthen with HN counterparts

and with the local populace.

Fostering Stability

Fostering stability encompasses long-term efforts that capitalize on capacity building and

reconstruction activities to establish conditions enabling sustainable development. This phase

emphasizes capacity building with the goal of transitioning responsibility to HN leadership and

security forces.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-5

MARINE CORPS APPROACH TO STABILITY OPERATIONS

The Marine Corps has long understood, as part of its legacy, that stability operations are precisely

the type of operations that Marine Corps operating forces, along with other elements of the joint

force, will be required to conduct, perhaps with increasing regularity. Therefore, the Marine Corps

approach to stability operations is to broaden its understanding and application of stability

activities beyond just offensive and defensive operations.

Etymology

Stability operations are the latest in a series of terminology nuances in an effort to add clarity and

definition to the increasingly large number of tasks US forces are required to conduct. In the 1930s

and 1940s the Marine Corps referred to these types of operations as small wars. In the 1980s, this

term evolved into “other expeditionary operations” and ultimately into “operations other than war.”

These terminology changes were an attempt to move away from the focus on war, become more

politically acceptable to intergovernmental partners, and address the myriad of additional missions

being performed by US forces; such as, noncombatant evacuation operations, peace operations,

counterdrug, FHA, and others.

Also, in the 1980s, joint doctrine expanded in breath and scope and adopted the term “military

operations other than war” or “MOOTW” as the overarching term to describe military tasks that

cannot be characterized as conventional combat operations. The Marine Corps, in an effort to

support evolving joint doctrine, adopted this change.

New terms stability, security, transition, and reconstruction were implemented by the Office of the

Secretary of Defense in DODD 3000.05 dated 28 November 2005. This directive defined stability

operations as, “Military and civilian activities conducted across the spectrum from peace to

conflict to establish or maintain order in States and regions.” This directive also defined military

support to stability, security, transition, and reconstruction as “Department of Defense activities

that support [US] Government plans for stabilization, security, reconstruction and transition

operations, which lead to sustainable peace while advancing US interests.”

At almost the same time, the United Nations (UN) term “peacekeeping operations” underwent

its own metamorphosis based on experiences in the Balkans. The term “peacekeeping” proved

insufficient to describe the types of peace operations being conducted globally. As a result, the

terms “peace enforcement” and “peacemaking” were adopted by the DOD to describe actions

being conducted in support of UN missions. This new terminology construct required a new

umbrella term resulting in the term “peace operations” with peace enforcement, peacemaking,

and peace building falling underneath.

In the early 2000s it became clear that US forces alone could not successfully accomplish

the range of tasks required to achieve stability in failed and failing states and that a whole

of government solution was required. With the Department of State (DOS) in the lead, the

United States Agency for International Development (USAID) began using the term “stability

operations” to describe the range of actions necessary to assist failed and failing states. This

term was viewed as less warlike than “military operations other than war” and, more

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-6

appropriately, described the increased range of actions required by military forces in operations

across the range of military operations. Operations in Iraq and Afghanistan have reinforced the

importance of the military contribution to stability operations functions and tasks.

Stability operations are discussed in JP 3-0, Joint Operations as various military missions,

tasks, and activities conducted outside the continental United States in coordination with other

instruments of national power to maintain or re-establish a safe and secure environment, provide

essential governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian relief

and includes missions such as nation assistance, FHA, and peace operations.

Aspects of Stability Operations

Stability operations are one of the Marine air-ground task force’s (MAGTF’s) missions. As part of its

small wars legacy, Marine Corps operating forces have conducted these types of operations along

with other elements of the joint force and they will conduct and/or support stability operations with

increasing regularity in the future.

The Marine Corp’s understanding of stability operations is in consonance with the DODI 3000.05

and JP 3-07, Stability Operations, definitions. Per the definition, stability operations—

Are OCONUS activities and as such, defense support of civil authorities is not considered a

stability operation.

Require unified action to harmonize all instruments of national power as well as those of the

host nation.

Are conducted to maintain or re-establish stability in a host nation.

Include activities that provide for a safe and secure environment and provide essential

governmental services, emergency infrastructure reconstruction, and humanitarian relief.

Certain characteristics that are typically associated with stability operations are as follows:

Occur across the range of military operations.

Occur in every phase of the joint campaign construct for major operations and campaigns.

Are the primary military contribution to stabilization in order to protect and defend a

population; facilitate the personal security of the people; and, thereby, create a platform

for political, economic, and human security.

Benefit from early transitions, which are preferable for an expeditionary force, but not

always possible.

Require continuous assessment from the strategic to the tactical levels.

Utilize civil-military operations (CMO) in a central integrating role in unified action.

Integrate communication (narrative) as a force multiplier for the collective stability effort.

MAGTF Execution of Stability Operations

The MAGTF’s expeditionary nature lends itself to frequently executing stability operations. In

the case of disaster relief operations, MAGTF air and ground lift capabilities may be tasked to

deliver relief supplies. In this case, extensive coordination between the MAGTF and civilian

organizations is critical to mission success. The MAGTF staff must be able to competently

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-7

navigate the labyrinth of civilian organizations in order to succeed. Civil affairs Marines

on the command element staff are ideal to support such coordination efforts.

STABILITY OPERATIONS TENETS

The following tenets apply to the planning, coordination, and execution of stability operations:

HN involvement. To the maximum extent possible, countries experiencing instability

must actively participate in defining objectives, conducting assessments, planning,

coordinating, and executing stability operations that lead to the resumption of their

authority and effective governance.

Joint operations. Stability operations usually require unified action from across the Services to

re-establish security, perform interim governance functions, repair critical infrastructure, and

enable the early resumption of HN economic and governance activities. Each Service will

be employed in accordance with its capabilities and address instability in the air, land, and

sea domains.

Assessment. Understanding the uniqueness of the operational environment and continually

updating information through assessment is vital to the planning and execution of stability

operations. It begins with a broad understanding of political, social, economic, cultural,

regional, and historical factors.

Comprehensive approach. Stability operations generally include participation from a large

number of USG departments and agencies referred to as the interagency. Most important is

the DOS because stability operations are conducted with ambassadorial (or deputy chief of

mission) coordination and approval. Other potential partners outside the USG referred to as

the interorganization include IGOs, NGOs, other nations, and multinational forces. Achieving

unity of effort among many organizations and activities, some with incongruent interests,

requires early and continuous coordination and integration.

Magnitude and duration may vary. Although mostly associated with actions following a major

campaign lasting years, a stability operation can include a crises response operation lasting only

a few days.

Security. Establishing security is a key prerequisite for stability operations and activities

and may require a range of defensive and offensive actions to create a safe environment for

stability-related efforts.

Transition lead responsibility. Since DOD has expeditionary capability and capacity in the

areas of command and control and logistics, it is often given the lead in certain aspects of

stability operations. However, early and continuous coordination and planning with the DOS

will better shape both the execution of the stability operation as well as assist in the transition to

the host nation. The responsibility for transition will normally be addressed by the DOS, UN,

coalition partners as well as the host nation.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

1-8

STABILITY OPERATIONS CRITERIA

A comprehensive understanding of what constitutes a stability operation is often difficult to

ascertain with the multitude of missions and activities. The following criteria, based on the joint

definition, that when met, determines whether an operation is or is not a stability operation. A

stability operation must—

Be conducted OCONUS.

Be conducted in coordination with USG agencies outside the DOD and or partner nations.

Be purposed to achieve at least one of the following:

Maintain objective or sustain a safe and secure environment.

Provide essential government services.

Reconstruct emergency infrastructure.

Provide humanitarian relief.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-1

CHAPTER 2

FUNCTIONS AND TASKS

The missions assigned to Marine Corps operating forces during stability operations may vary

depending upon the security environment, the authority and responsibility of the forces, and

the presence and capacities of NGOs, IGOs, nonstate actors (threat, friendly, neutral) and other

non-DOD departments and agencies. In some cases, these actors will be well established before

stability operations begin. In others, Marine Corps operating forces will have to operate before

other actors can have a significant presence and may, in some cases, be expected to lead a

nonsecurity effort until other more appropriate organizations take responsibility for the task.

Marine Corps support to the range of stability-related tasks can take the form of individual

augmentation or logistics, communications, legal, engineering, or medical support. As with all

support-related tasks, the type of support (direct, close, mutual, or general) as well as the degree

of support must be specified by the establishing authority or agreed mutually by the supporting

and supported commanders.

FUNCTIONS

JP 3-07 identifies five stability operations functions used by joint force planners to guide the

planning and conducting of stability operations. Their principal purpose is to ensure that a

comprehensive plan is developed that includes all stability-related activities. These functions are—

Security

Humanitarian assistance

Economic stabilization and infrastructure

Rule of law

Governance and participation

These functions were first codified in the DOS publication Guiding Principles for Stabilization

and Reconstruction. This publication provides a framework for stabilization efforts that stems

from the policies, doctrine, and training of civilian departments and agencies across both the

USG and foreign governments.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-2

TASKS

The Marine Corps recognizes six core stability tasks that flow directly from stability functions.

These stability tasks are—

Establish civil security.

Provide humanitarian assistance.

Support and/or provide restoration of essential services.

Support establishment of civil control.

Support economic and infrastructure development.

Support to governance.

The six core stability tasks and their numerous subtasks focus Marine Corps efforts toward desired

conditions. Normally, Marine Corps operating forces support stability operations in the initial phase

until adequate security is achieved and HN or other government agencies can perform their

established role. In other cases, such as a failed state, Marine Corps operating forces may be required

to participate in a broader range of tasks and participate before and/or beyond the initial phase.

The six core stability tasks are interrelated whereby achieving a specific objective or establishing

certain conditions often requires performing a combination of related tasks. For example, the tasks

required to provide a safe, secure environment for the local populace may require Marine Corps

operating forces to participate in ending hostilities, isolating belligerents and criminal elements,

demobilizing armed groups, eliminating explosives and other hazards, and providing public order

and safety.

The size of the force and combination of tasks necessary to stabilize conditions depend on the

situation in the operational area. When a functional, effective HN government exists, Marine Corps

operating forces work through and with local civil authorities. Together, they restore stability and

order and may be required to reform the security institutions that foster long-term development. In

this situation, the size of the force and the scope of the mission are more limited. However, in a

worst-case scenario, the security environment is in chaos, and the state is in crisis or has failed

altogether. In this situation, Marine Corps and other forces focus on the core tasks that establish a

safe, secure environment and address the immediate humanitarian needs of the local populace.

Marine Corps forces may lead and/or support the execution of these core tasks. In some cases,

Marine Corps operating forces may lead a core task until the HN or other government agencies are

capable of performing their leadership role. Often this requires a level of security that allows

relative safety for those personnel.

All six core tasks have a security component ideally performed by Marine Corps operating forces.

However, Marines may provide other support (e.g., logistics, engineering) to enable the success of

civilian agencies and organizations.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-3

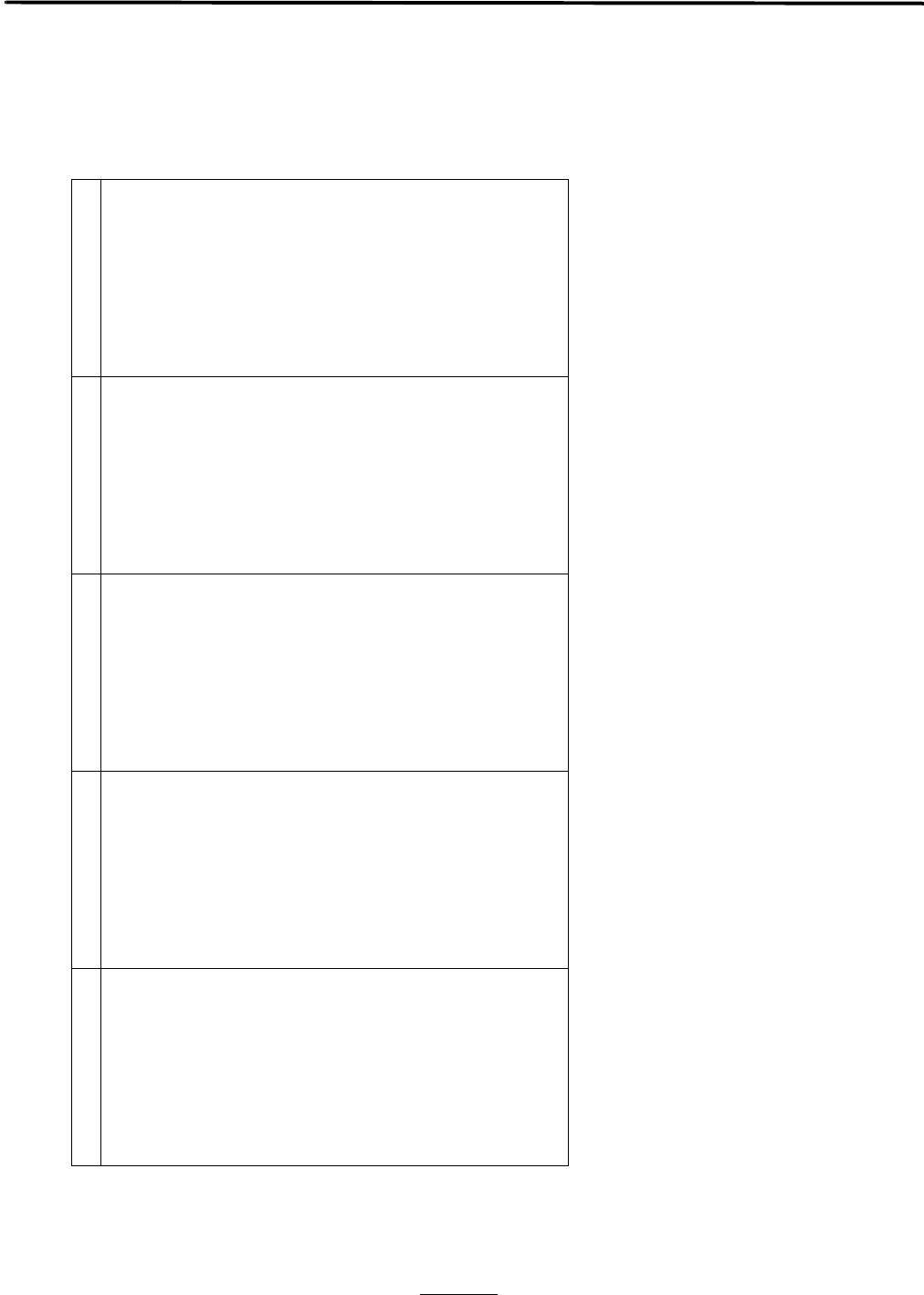

Establish Civil Security

Civil security is the provision of security for state entities and indigenous populations and

institutions, including protection from internal and external threats. Establishing a safe, secure,

and stable environment helps obtain local support for the overall operation. As soon as the HN

security forces can perform this task, Marine Corps operating forces transition civil security

responsibilities to them. Within the security functional area, transformation tasks focus on

developing legitimate, sustainable, and stable security institutions. Civil security helps set

conditions for enduring stability.

Marine Corps forces help establish civil security by performing a number of subordinate tasks.

During the initial response phase, Marine Corps operating forces may execute the tasks on their

own because the host nation lacks capability or the security situation prevents their involvement.

In the transformation phase and fostering sustainability phase, Marine Corps operating forces

transition to building partner capacity missions that improve the capability and capacity of HN

security forces.

Depending on the situation, establishing civil security may include seven subtasks.

Enforce Cessation of Hostilities, Peace Agreements, and Other Arrangements. Marine Corps operating

forces perform peacekeeping or peace enforcement missions. Peacekeeping missions may involve

monitoring, facilitating confidence building measures, and investigating alleged violations.

Peace enforcement missions may involve working with parties that have not agreed to end

hostilities and to compel compliance with sanctions or resolutions designed to maintain peace

and order. Marine Corps forces enforce cease fires with measures such as patrols, guard posts,

remote sensors, checkpoints, and possibly a focus on a buffer zone that separates belligerents.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may also be required to supervise

adversary disengagement, identify or neutralize adversaries, provide security for negotiations, and

build HN capacity.

Determine Disposition and Composition of National Armed and Intelligence Services. Host-nation

security forces may include military, police, border security, various infrastructure protection

forces, intelligence organizations, and nonstate security actors. Determining host-nation security

forces disposition and composition enable proper planning of stability operations and help determine

the level of effort needed in supporting the host-nation security forces.

Host nation military forces may include active duty or reserve component army, marine corps,

navy, air force, coast guard, or special operations forces. Units may be postured for territorial

defense, home guard functions, or expeditionary missions and are normally subordinate to a

ministry of defense.

Constabulary forces may be local, regional, and national police forces and fall under the ministries

of defense or interior. Normally, these forces focus on internal threats, law and order, and crime

prevention and response. Specialized units may address issues such as terrorism, narcotics,

organized crime, corruption, or human trafficking. Police forces are normally subordinate to the

primary civilian official in their jurisdiction (e.g., mayor, governor), with national police normally

subordinate to an interior minister. Police forces may have overlapping jurisdictions with other

security forces, including military units. Border security forces along the nation’s boundaries are

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-4

normally subordinate to the ministries of defense or interior. They may include customs and

immigration organizations, although these may fall under a different ministry.

A wide variety of infrastructure protection forces may exist. These forces have responsibility

for securing power facilities, refineries, shipyards, telecommunications sites, and other locations

and may be subordinate to the relevant ministries, regional or local governments, or to the

facility administrators.

One or more intelligence organizations may exist, reporting to the ministry of defense or interior,

a separate intelligence chief, or other organization. These organizations focus on foreign concerns,

domestic matters, or both.

Nonstate security actors may include tribal militias, private security firms, and other

nongovernmental armed organizations.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may include planning for

disposition of security institutions; identification of future roles, missions, and structures;

vetting key officials; and conducting security force assistance and building HN capacity to

protect military structure and military capability.

Support Disarmament, Demobilization, and Reintegration. Effective disarmament, demobilization,

and reintegration reduce drivers of conflict, build a stable society, and create a legitimate state

monopoly over the means of violence. These matters often require informal negotiations as

peace agreements often focus on ending hostilities and avoiding lesser but still important

subsequent matters.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces include negotiating terms,

establishing weapons control programs, establishing monitoring programs and/or demobilization

camps, disarming combatants, collecting unauthorized weapons, and reintegrating combatants

back into society.

Conduct Border Control, Boundary Security, and Freedom of Movement. Border security reinforces

national sovereignty and prevents interstate conflict. This includes physical security provided by

military, border, or coast guard forces while customs officials regulate the flow of people, animals,

and goods across the border, maritime terrain, or into ports of entry. Border control measures

regulate immigration, control movements of the local populace, collect excise taxes or duties,

limit smuggling, and control the spread of disease vectors through quarantine.

When confronted with an internal threat, the host nation secures its borders to prevent an influx of

foreign fighters and other external threats and keep insurgents from getting support or using

neighboring countries as sanctuaries. In some situations, the host nation secures its intranational

boundaries to prevent factional conflict. In addition to border control, freedom of legitimate

international and internal movement is essential for normal economic and social interaction.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may include conducting border

security operations, supporting HN border security efforts, monitoring the border, establishing

movement rules, dismantling roadblocks, establishing checkpoints, training and equipping border

control and boundary security forces, and ensuring freedom of movement.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-5

Support Identification Programs. Identification programs support security, governance, and the rule

of law and document individuals, businesses, and corporations. These measures support legitimate

activity, enable government regulation, and generate revenue. Other purposes include ensuring

legitimate political participation; adjudicating property disputes; restricting the activities of

individuals who have perpetrated major crimes, atrocities, or abuses; and isolating or

neutralizing belligerents. Effective population identification methods facilitate establishing

a secure and stable environment for the population.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may include securing

documents, establishing identification programs, and enforcing use of and adherence to the

identification programing.

Protect Key Personnel and Facilities. Throughout stabilization efforts, Marine Corps operating

forces may ensure that high priority personnel and facilities have protection, which may include

arrangements for emergency medical support. With relatively little effort, belligerents can

eliminate a critical partner or destroy a complex facility and either event can significantly set

back and undermine mission success.

Subordinate tasks may include protection of stabilization and reconstruction personnel and

resources, provision of emergency logistic support, protection of cultural sites, and protection

of critical infrastructure and civil records. Other tasks may include protecting military facilities

and lines of communications, identifying and disposing of ordnance, building HN capacity to

provide own protection, and advising and assisting with HN security forces protection efforts.

Clear Explosive Ordnance. Explosive ordnance includes unexploded explosive ordnance;

mines; loose, stockpiled, or deteriorated ordnance; and illicit ordnance caches. Marine Corps

operating forces aim to prevent adversaries from acquiring these items and prevent these

hazards from harming civilians and friendly forces. Subordinate efforts may include explosive

ordnance disposal.

Provide Humanitarian Assistance

Conflict, especially extended conflict, results in human suffering caused by acute shortages of water,

food, shelter, clothing, bedding, and medical aid. Marine Corps forces are often the first response

force on the scene and support HN efforts to provide humanitarian assistance with logistics,

distribution, communication, and other relief capabilities and supplies. Most often, Marine

Corps operating forces work in support of other USG departments and agencies, the host nation,

or others. Depending on the situation, providing humanitarian assistance may include three

subtasks, providing local security, distributing relief supplies, and supporting dislocated

civilians (DC).

Provide Local Security. Humanitarian assistance efforts are often hampered by lawlessness

caused by looters, muggers, and robbers. Often these criminal elements take to the street as

gangs and hamper local efforts to provide needed aid and assistance. Marine Corps forces will

provide local security to humanitarian relief efforts, protect the effected population, relief

personnel, and relief supplies.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-6

Distribute Relief Supplies. During most US involvement in disaster relief operations, US forces

will not be called to assist. However, there may disasters or security situations so severe that

DOD capabilities are requested. In most cases, the largest contribution is air and ground lift

transportation of relief supplies to distributing organizations in the affected area. It is important

to note that US forces should only deliver supplies directly to the population when absolutely

necessary. Otherwise, relief supplies should be delivered to the host nation, indigenous

populations and institutions, USAID, IGO, or another sanctioned entity. This concept is

referred to as wholesale distribution versus retail distribution. The MAGTF should stay in

the wholesale distribution business and only conduct retail distribution when

absolutely necessary.

Support Dislocated Civilians. Dislocated civilians may have been forced to leave their homes due

to violence, natural disaster, and environmental conditions such as drought. Dislocated civilians

are particularly vulnerable to starvation, dehydration, disease, or additional acts of violence.

These persons can greatly complicate relief efforts. Most often, Marine Corps operating forces

support DCs by supporting organizations such as the UN High Commissioner for Refugees or

other UN agency that leads DC relief efforts. Occasionally, Marines provide direct assistance

and security to DC camps.

Support and/or Provide Restoration of Essential Services

Restoring essential services to local expectations of normalcy allows a population to return

to their routine, daily activities and prevents further destabilization. Host nation government

or civilian relief agencies work best to restore and develop essential services. In most cases,

local, international, and US civilian agencies or organizations arrived in country long before

US forces. However, when these organizations are not established or lack the necessary

capacity, Marine Corps operating forces provide support in a limited capacity until the civilian

organizations are established.

Essential services are often grouped under the acronym SWEAT (sewage, water, electricity,

academics, and trash), as well as medical, safety, and other considerations (shelter, transportation,

communications, etc.). The MAGTF must be prepared to conduct necessary coordination with

civilian entities to ensure progression in or restoration of SWEAT and medical, safety, shelter,

transportation, and communications services. Civil affairs Marines are ideal for this coordination and

can support the staff in planning for operations that support restoration of essential services. In

extreme cases, Marine Corps combat engineers and utilities personnel may need to undertake

projects that temporarily provide services to the local population until appropriate civilian

organizations take over.

Support Establishment of Civil Control

Civil control is the ability for the sanctioned local leadership to manage the disputes and conflicts

within the population effectively and fosters the rule of law. The rule of law refers to a principle

of governance in which all persons, institutions, and entities (public and private, including the

State) are accountable to laws that are publicly promulgated, equally enforced and independently

adjudicated, and are consistent with international human rights norms and standards. Civil control

is based on a society that ensures that citizens live in a safe society in which individuals and

groups adhere to the rule of law. The rule of law provides equal access to a justice system that

is consistent with international human rights standards. This is a long-term process developed

by civilian entities.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-7

Marine Corps forces support civil control and the rule of law in order to improve the capability,

capacity, and legitimacy of HN judicial and corrections systems by providing training and support to

law enforcement and judicial personnel. The focus is to implement temporary or interim capabilities

to lay the foundation for HN or interorganizational development of this sector.

Depending on the situation, establishing security for civil control may include six subtasks, which

are discussed in the following subparagraphs.

Support Establishment of Public Order and Safety. Public order is a condition in which laws are

enforced equitably. The lives, property, freedoms, and rights of individuals are protected; criminal

and politically-motivated violence is minimal; and criminal elements (from looters and rioters to

leaders of organized crime networks) are pursued, arrested, and detained. Public safety permits

people to conduct their daily lives without fear of systematic or large-scale violence. Long-term

sustainability of reforms depends on the achievement of public order and safety.

Subordinate tasks may include population protection, ensuring access to endangered

populations, performance of civil police functions, safeguarding witnesses and evidence,

population control, crowd control, and security for criminal justice and security institutions.

Support Law Enforcement and Police Reform. Law enforcement and policing operations comprise

an essential component of civil control. Typically, civilian agencies provide support for law

enforcement and police reform. Sometimes HN civilian police forces succumb to corruption and

locals distrust them. As a result, US or HN forces with law enforcement experience fill the void

and provide this support until civilian agencies or organizations can do so.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may include identification of crime

evidence, identification and detention of perpetrators, support vetting and accounting, deployment of

police trainers and advisors, assessment of police facilities and systems.

Support Justice System Reform. Stabilization requires the populace to perceive their nation’s the

justice system as legitimate, fair, and effective. Justice system reform activities aim to achieve

broad institutional reform by updating legal statutes and reorganizing fundamental justice system

structures to ensure basic fairness and protect human rights. While civilian agencies typically lead

such reform efforts, military forces sometimes establish and maintain the security necessary to

facilitate future efforts.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may include support to

communications and provide security to personnel and facilities.

Support Corrections Reform. Corrections reform is an integral part of broader security sector

reform. Corrections reform includes building HN penal system capacity by restoring institutional

infrastructure, providing oversight of the incarceration process, and training HN personnel to

internationally accepted standards. Tasks also include instituting a comprehensive assessment of the

prisoner population, determining the status of prisoners, and establishing procedures to help

reintegrate political prisoners and others unjustly detained or held without due process into society.

Subordinate tasks performed by Marine Corps forces may include identification of detention,

correction, or rehabilitative facilities; preservation of penal administrative records; assessment of

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-8

prison populations and conditions; implementation of humanitarian standards in prisons;

provision of emergency detention facilities; deployment of penal trainers and advisors;

refurbishment of prison facilities at key sites; coordination of jurisdiction and handover; and

facilitation of international monitoring.

Support War Crimes Courts and Tribunals. Although the international community oversees the

conduct of war crimes courts and tribunals, Marine Corps operating forces may provide support for

their activities as part of the broad process of justice system reform. Support may include protecting

witnesses; identifying, securing, and preserving evidence for courts and tribunals of war crimes and

crimes against humanity; supporting the investigation, arrest, and transfer of war criminals; and

coordinating efforts with other agencies and organizations. Subordinate tasks may include security

of facilities and establishment of an atrocity reporting system.

Support Public Outreach and Community Rebuilding Programs. The reconciliation process requires

public outreach and community rebuilding while promoting public respect for the rule of law.

Tasks performed by Marine Corps operating forces may include training, advising, and assisting

HN agencies in developing public access to information and assessing the needs of vulnerable

populations, such as women, children, and the elderly. Subordinate tasks may include supporting

the ability of HN agencies to establish information programs, develop public access to information,

and assess population needs.

Support Economic and Infrastructure Development

In post-conflict and fragile states, HN actors often have the best qualifications to lead efforts

to restore and help develop HN economic capabilities, not USG departments and agencies,

IGO’s, and civilian relief agencies. The goal is to establish conditions so that the host nation can

generate its own revenues and not rely upon outside aid. Security considerations or other factors

may make HN actors incapable of assisting initially. In these instances, Marine Corps forces

may support efforts to assist the host nation begin the process of achieving or preserving

sustainable economic development. Preserving assets such as production facilities, hospitals,

universities, existing companies, and markets dramatically reduces the time required to

re-establish a sustainable level of economic activity.

Before implementing any activities, Marine Corps forces must first assess the economic and

infrastructure situation in their operational area. This assessment should be based on local norms

and should identify and prioritize the sources of instability that threaten effective economic and

infrastructure development.

Subordinate tasks may require Marine Corps operating forces to protect natural resources and

the environment as well as support—

Economic generation.

Public sector investment programs.

Agricultural investment programs.

Transportation infrastructure programs.

Telecommunications infrastructure programs.

General infrastructure reconstruction programs.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-9

Depending on the situation, supporting economic and infrastructure development may include

five subtasks, which are discussed in the following paragraphs.

Support the Protection of Natural Resources and Environment. Marine Corps forces with HN, US,

and international partners assess locations and amounts of vital natural resources. Vital natural

resources include, but is not limited to, oil, gas, strategic minerals, diamonds, and timber. Marine

Corps forces support the security of vital natural resources collaborating with HN, US, and

international actors to assess and secure access to vital natural resources, including existing HN

extraction facility locations and capacities and movement of these resources to markets.

Support Economic Generation and Enterprise Creation. Creating jobs is central to any economic

recovery program. Many activities fall under the task of job creation, including immediate, short-

term opportunities that yield quick impact or the development of more enduring livelihoods in the

civil service or private sector. Marine Corps forces implement initiatives to provide immediate

employment as this initiative gets people back to work and gets money flowing, even if only

temporarily. These initiatives may include development of quick impact public sector jobs such as

collecting trash, cleaning up public places, installing generators, and rebuilding infrastructure such

as roads, bridges, and electric grids.

Support Agricultural Development Programs. A nation’s agriculture sector serves as the foundation

of food security, defined as including both physical and economic access to food that meets

people’s dietary needs. Beyond supporting food security, a viable market economy relies on an

integrated agricultural development with links through all levels of a nation’s economy. Marine

Corps forces may provide security for post-harvest storage facilities and support the rebuilding of

small-scale irrigation systems and repair small-scale infrastructure such as storage. Commander’s

emergency response program funds may be used to support these programs if existing authorities

approve their use within the operational area.

Support Restoration of Transportation Infrastructure. United States forces may be required to assess

the overall condition of national transportation infrastructure—airports, roads, bridges, railways,

and coastal and inland ports, harbors, waterways—including facilities and equipment. For each

infrastructure, US forces assess its management organization and facilities, maintenance, and

security. Marine Corps forces assess the transportation infrastructure in their operational area

and provide an infrastructure assessment in terms of status, capacity, future requirements, and

potential shortfalls given damage from conflict, natural disaster, or neglect. Marine Corps forces

may conduct expedient repairs of roads and runways. Ports and airfields are of special importance

to the economy and to the perceived legitimacy of the HN government and often receive priority

status for restoration.

Support General Infrastructure Reconstruction Programs. As either a joint force or a MAGTF,

Marine Corps forces may conduct expedient repairs or support construction of new facilities to

support the local populace. Expedient measures include providing power; restoring structural

integrity; providing heat, lighting, and plumbing; or installing doors and windows. Prioritized

facilities likely include schools, medical clinics, municipal buildings, and water and sewage

management facilities.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

2-10

Support to Governance

Governance is the state’s ability to serve the citizens through the rules, processes, and behavior

by which interests are articulated, resources are managed, and power is exercised in a society,

including the representative participatory decision-making processes typically guaranteed under

inclusive, constitutional authority. Effective, legitimate governance ensures these activities

are transparent, accountable, and involve public participation. Elections do not necessarily

ensure these outcomes. In societies divided along ethnic, tribal, or religious lines, elections

may further polarize factions. Generally, representative institutions based on universal suffrage

offer the best means fostering governance acceptable to the majority of the citizens. If the

HN government or community organizations cannot provide governance, some degree of

military support may be necessary. See JP 3-24, Counterinsurgency, for more information

on governance and COIN operations

Stability operations often occur in failed or fragile state situations or when the HN government has

difficulty resolving stabilization and reconstruction challenges. In some cases, HN governments can

function and exercise their sovereign responsibility. In these cases, international actors, including

Marine Corps forces, support HN government authorities. However, if the HN government is

dysfunctional or absent, military forces may be obligated to provide interim governance as a

transitional military authority until the host nation establishes a responsible civilian authority.

Depending on the situation, support to governance may include three subtasks, which are

discussed in the following paragraphs.

Support Transitional Administrations. Stabilization efforts, particularly in a failed state, incorporate

a series of transitional governmental administrations until the host nation establishes a permanent

arrangement. In some cases, US forces may initially be assigned responsibility as a transitional

military authority, to be followed by an external provisional civilian authority controlled by the USG,

a coalition, or other IGO. Responsibility eventually transfers to HN authorities.

Support Development of Local Governance. Normally, civilian agencies support local governance

and building local governance capacity. Marine Corps forces may support civilian agencies in

improving governance in local communities. Local governance provides the foundation on

which to develop higher-level governance. Generally, unit operational areas align with HN

political boundaries (e.g., provinces, districts), which helps integrate governance with assigned

Marine security requirements.

Support Elections. Elections represent progress and stability. More importantly, they legitimize the

government by reflecting the population’s endorsement. Marine Corps forces primarily establish

and maintain secure conditions that allow the host nation to conduct campaigning and elections.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

3-1

CHAPTER 3

PLANNING FOR STABILITY OPERATIONS

Planning stability operations requires consideration of many factors, some not generally considered

by military planners. The centrally important planning consideration is that a long-term view

is required. Stability operations are, at their essence, political with interlocking instruments of

diplomacy, economics, information, and military action. The stability operations environment

requires an inclusive approach, which extends beyond the joint community and into the interagency.

Early collaboration with interagency partners is a critical component to reduce risk and help ensure

success. In operating in these complex environments, Marines must understand interagency partner

capabilities and limitations and integrate them into all actions from the early planning phase through

execution and transition. As planning is widely discussed in other doctrinal publications such as

Marine Corps Warfighting Publication (MCWP) 5-10, Marine Corps Planning Process, this chapter

focuses on planning considerations unique to stability operations. Failure to provide adequate

planning attention on any of these considerations may compromise mission success.

UNIFIED ACTION

Unified action coordinates and/or integrates the activities of governmental and nongovernmental

entities with military operations to achieve unity of effort. Unity of effort, the product of unified

action, is defined as the “coordination and cooperation toward common objectives, even if the

participants are not necessarily part of the same command or organization, which is the product of

successful unified action.” (JP 1, Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States)

One of the defining features of contemporary stabilization environments is the array of participants

present in the theater of operations. The range of external stakeholders could include various USG

departments and agencies, allies (who themselves often have a multiagency presence), IGOs, NGOs,

and private sector interests. Despite the differing organizational cultures, experiences,

and timelines that inevitably will exist among stakeholders, it is imperative that there be a shared

understanding of the international objectives and operational environment, cooperative planning and

assessment, and coordinated, integrated (when appropriate) actions and activities—unified action.

Stabilization efforts are primarily the responsibility of development and Foreign Service

personnel from across the USG. The DOS—

Is responsible for leading a whole of government approach to stabilization.

Leads and coordinates US interagency participation in a comprehensive approach to stabilization

efforts that include not only the United States but also the host nation, other nations, IGOs,

cooperating NGOs, and other participants.

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

3-2

When stabilization activities occur in a nation state, the primary coordination occurs with the

country team. The GCC formulates a theater security cooperation plan with the country teams

that are located within the region.

The interrelated responsibilities and authorities of the participants in stability operations often

create friction. Achieving unity of command in stability operations is not always possible.

Instead, participants strive to unify actions to achieve unity of effort. The MAGTF commander

must realize this and be comfortable with its implications throughout the operation.

Detailed planning and good personal relationships are critical for unity of effort. Clear lines of

responsibility—ranging from the ambassador, through the joint force commander (JFC), to the

MAGTF commander—are essential.

Stability operations often include coalition partners. This is especially true in humanitarian

assistance and disaster-relief operations. Coalition partners bring expertise and needed capabilities

that must be integrated into the operation as part of the unified action. Reference JP 3-08,

Interorganizational Coordination During Joint Operations, and Marine Corps Tactical

Publication (MCTP) 3-03C, MAGTF Interorganizational Coordination, for additional information.

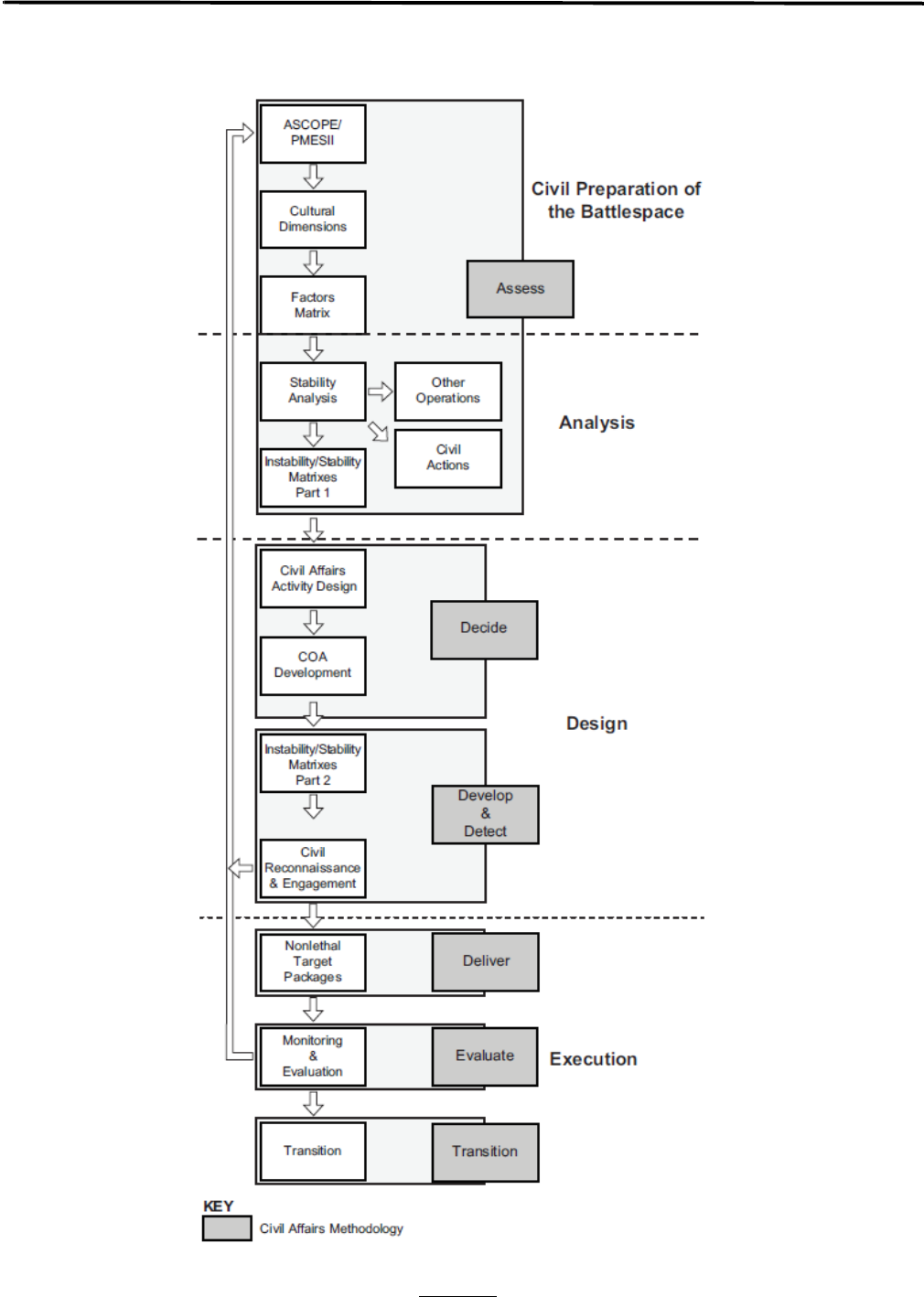

CIVIL-MILITARY OPERATIONS

Civil-military operations (CMO) are those civil-military activities planned and performed by

military forces to maintain, influence, or exploit relations among military forces, governmental

agencies, and nongovernmental civilian organizations and in order to re-establish the functions

normally the responsibility of the local, regional, or national government. Civil-military

operations are inherent to all military operations that require interorganizational coordination

and the management of local populations as it relates to executing the MAGTF mission.

Civil-military operations planning ensures careful analysis of the civil landscape and ensures

incorporation of civil considerations into the overall planning process. Civil-military operations

planning includes the design and integration of civil-military activities into MAGTF plans in

support of the commander’s objectives. It is unique in that much of what is planned involves

military forces to maintain, influence, or exploit relations among military forces, governmental

agencies, nongovernmental civilian organizations, and the civilian populace to achieve the

commander’s desired end state.

Proficient CMO planners are skilled at providing the commander and staff with situational

awareness and in creating a shared understanding of the problem from a civil-military perspective.

Civil preparation of the battlespace is used to examine civil considerations in support of mission

analysis and the overall intelligence preparation of the battlespace process. Civil preparation of

the battlespace is conducted through the framework of METT-T [mission, enemy, terrain and

weather, troops and support available-time available] in order to focus on civil aspects as it relates

to the overall operational environment and mission accomplishment. Civil preparation of the

battlespace uses a myriad of methods to specifically analyze different aspects of civil information

and assess the civil impact of friendly, adversary, and external actors, as well as the local

MCWP 3-03 Stability Operations

3-3

populace, on MAGTF operations and the achievement of objectives. The CMO planner can

effectively build understanding of CMO considerations as the plan is transitioned to current

operations and executed by elements of the MAGTF.

Products of CMO planning might include the CMO staff estimate, CMO-related tasks in the

basic order, and the associated annex G/appendices/tabs. One coordination tool available to the

commander that civil affairs Marines provide is the civil-military operations center. The civil-

military operations center is a civil-military coordination element, normally comprised and ran by

civil affairs Marines, established to plan and facilitate coordination of MAGTF activities within

indigenous populations and institutions, the private sector, IGOs, NGOs, multinational forces,

and other governmental agencies. The civil-military operations center facilitates continuous

coordination among the key participants with regard to CMO from local levels to international

levels within a given operational area and develops, manages, and analyzes the civil inputs to the