OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER ii

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

CONTRIBUTING AUTHORS

Guadalupe Capozzi

Silas Cha

Daryl Johnson

EDITOR

Neomi Daniels

CONTENT REVIEWERS

Katie Conklin

Greg Kennedy

Rene Paredes

Jacqui Shehorn

Kelsey Smith

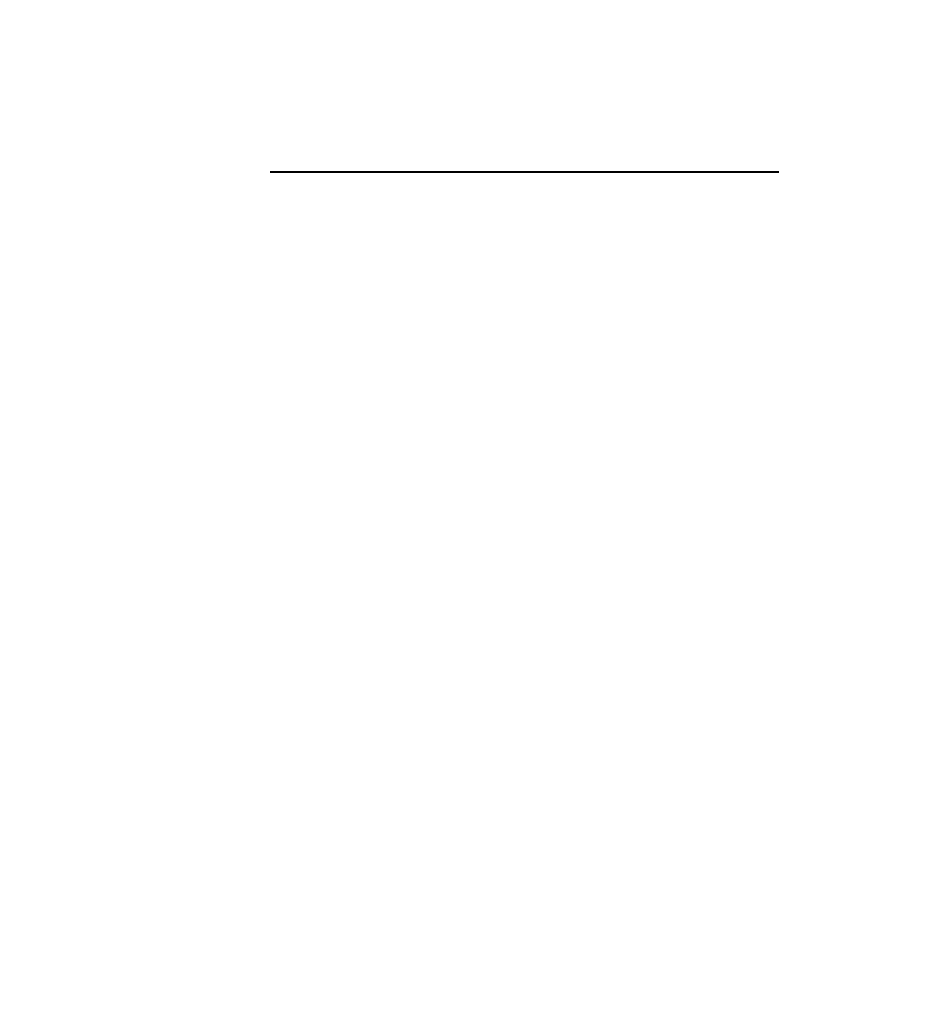

COVER IMAGE

Image by Jackson David, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

COPYRIGHT

Produced and distributed under a Creative Commons License in June 2022.

“Our Lives: An Ethnic Studies Primer” by Vera Kennedy and Rowena Bermio is licensed under

CC BY-NC 4.0.

The contents of this book were developed under an Open Textbooks Pilot grant from the Fund

for the Improvement of Postsecondary Education (FIPSE), U.S. Department of Education.

However, those contents do not necessarily represent the policy of the Department of

Education, and you should not assume endorsement by the Federal Government.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER iii

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Module 1. The Significance of Ethnic Studies............................................................................... 1

Learning Objectives ................................................................................................................................... 1

Key Terms & Concepts ............................................................................................................................... 1

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................... 2

Application 1.1 Acknowledging Indigenous People’s Land ................................................................... 3

Understanding Race................................................................................................................................... 4

Application 1.2 Breaking the Illusion of Skin Color ............................................................................... 4

Race-Ethnic Relations Today...................................................................................................................... 6

Application 1.3 Leadership Development through Intergroup Dialogue ............................................. 8

Race-Ethnic Group Perceptions ................................................................................................................. 8

Explanations of Racial Inequalities .......................................................................................................... 10

Table 1. Structural Factors of Social Position & Intergroup Relations ............................................... 11

Application 1.4 Intergroup Dialogue & Social Change ........................................................................ 13

Application 1.5 Social Distancing by Race & Ethnicity ........................................................................ 15

Reality of Inequality ................................................................................................................................. 16

Table 2. Indicators of Racial Ethnic Inequality in the United States .................................................. 16

Table 3. Indicators of Racial Ethnic Inequality in the United States .................................................. 16

Application 1.6 Housing Discrimination .............................................................................................. 18

Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 18

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................... 18

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................... 18

References ............................................................................................................................................... 19

Module 2. Our Power & Identity ................................................................................................ 21

Learning Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 21

Key Terms & Concepts ............................................................................................................................. 21

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 22

Collective Culture ..................................................................................................................................... 22

Social & Cultural Bonds ....................................................................................................................... 23

Biographical Reflection 2.1 When Did You Become Black? ................................................................ 25

Levels of Culture ................................................................................................................................. 26

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER iv

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Groups & Organizations ...................................................................................................................... 26

Application 2.1 Your Regional Culture ................................................................................................ 27

Doing Culture ...................................................................................................................................... 29

Identity Formation & Politics ................................................................................................................... 30

Intersectionality .................................................................................................................................. 31

Application 2.2 The Privilege & Oppression of Intersectionality ........................................................ 32

Globalization & Identity ...................................................................................................................... 33

Identity Today ..................................................................................................................................... 34

Cultural Change & Adaptation ................................................................................................................ 35

Othering & Belonging .............................................................................................................................. 36

Biographical Reflection 2.2 One Times Three Equals One .................................................................. 38

Application 2.3 The Meaning & Impact of Your Story ........................................................................ 39

Application 2.4 Privilege & Life Chances ............................................................................................. 40

Biographical Reflection 2.3 Single Mother Gets a Bad Rap ................................................................ 41

Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 41

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................... 42

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................... 42

References ............................................................................................................................................... 42

Module 3. Our Story: Native Americans ..................................................................................... 45

Learning Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 45

Key Terms & Concepts ............................................................................................................................. 45

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 45

Indigenous Peoples of the Americas ....................................................................................................... 46

Contact & Conflict with the “Old World” ................................................................................................ 46

English Colonial Period ............................................................................................................................ 47

Westward Expansion............................................................................................................................... 49

Application 3.1 Shifting Perspective: Cherokee Indians ..................................................................... 50

The 20

th

Century ...................................................................................................................................... 53

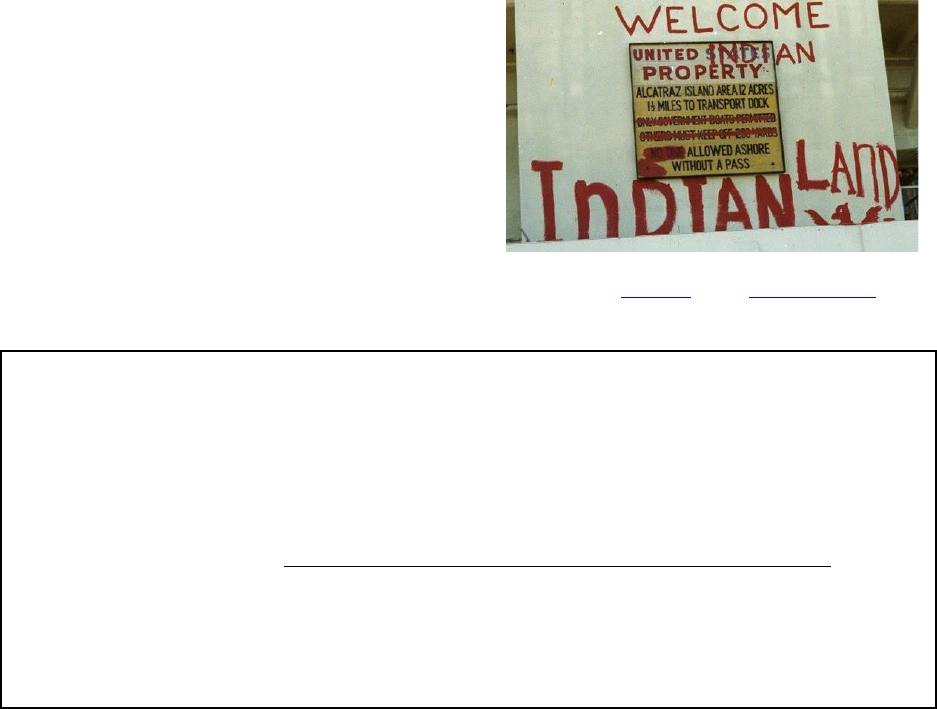

Application 3.2 Shifting Perspective: Alcatraz Proclamation .............................................................. 54

Application 3.3 Our Fires Still Burn ..................................................................................................... 55

The Recent Past ....................................................................................................................................... 55

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER v

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 56

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................... 56

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................... 56

References ............................................................................................................................................... 57

Module 4. Our Story: African Americans .................................................................................... 58

Learning Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 58

Key Terms & Concepts ............................................................................................................................. 58

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 59

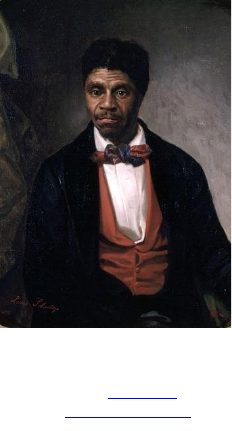

Colonial Period to Reconstruction .......................................................................................................... 59

Application 4.1 Shifting Perspective: Benjamin Banneker .................................................................. 62

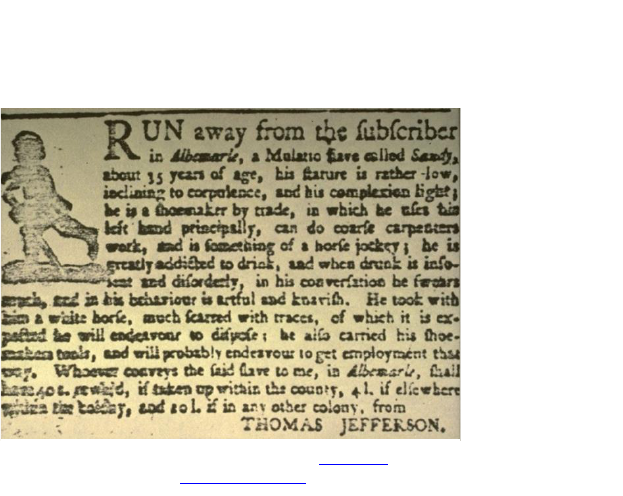

Application 4.2 Shifting Perspective: Justifying Slavery ...................................................................... 64

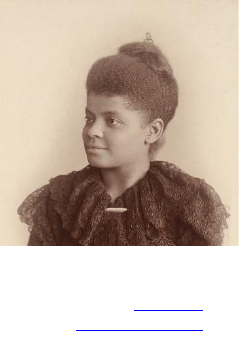

1877 to WWII .......................................................................................................................................... 67

Application 4.3 Shifting Perspective: What is Race? .......................................................................... 69

Civil Rights Movement of the 60s & 70s ................................................................................................. 71

Application 4.4 Shifting Perspective: Letter from Birmingham .......................................................... 72

The Recent Past ....................................................................................................................................... 73

Biographical Reflection 4.1 A Proud American, or a Proud African American? ................................. 74

Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 75

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................... 75

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................... 75

References ............................................................................................................................................... 75

Module 5. Our Story: Asian Americans ...................................................................................... 77

Learning Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 77

Key Terms & Concepts ............................................................................................................................. 77

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 77

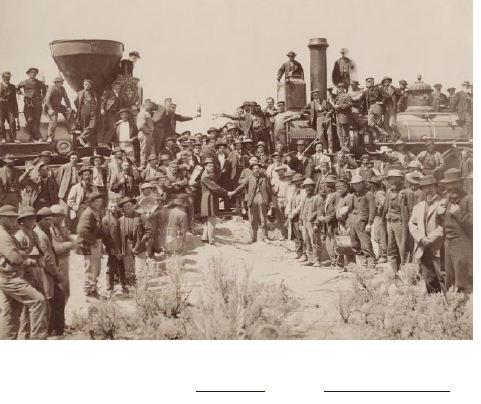

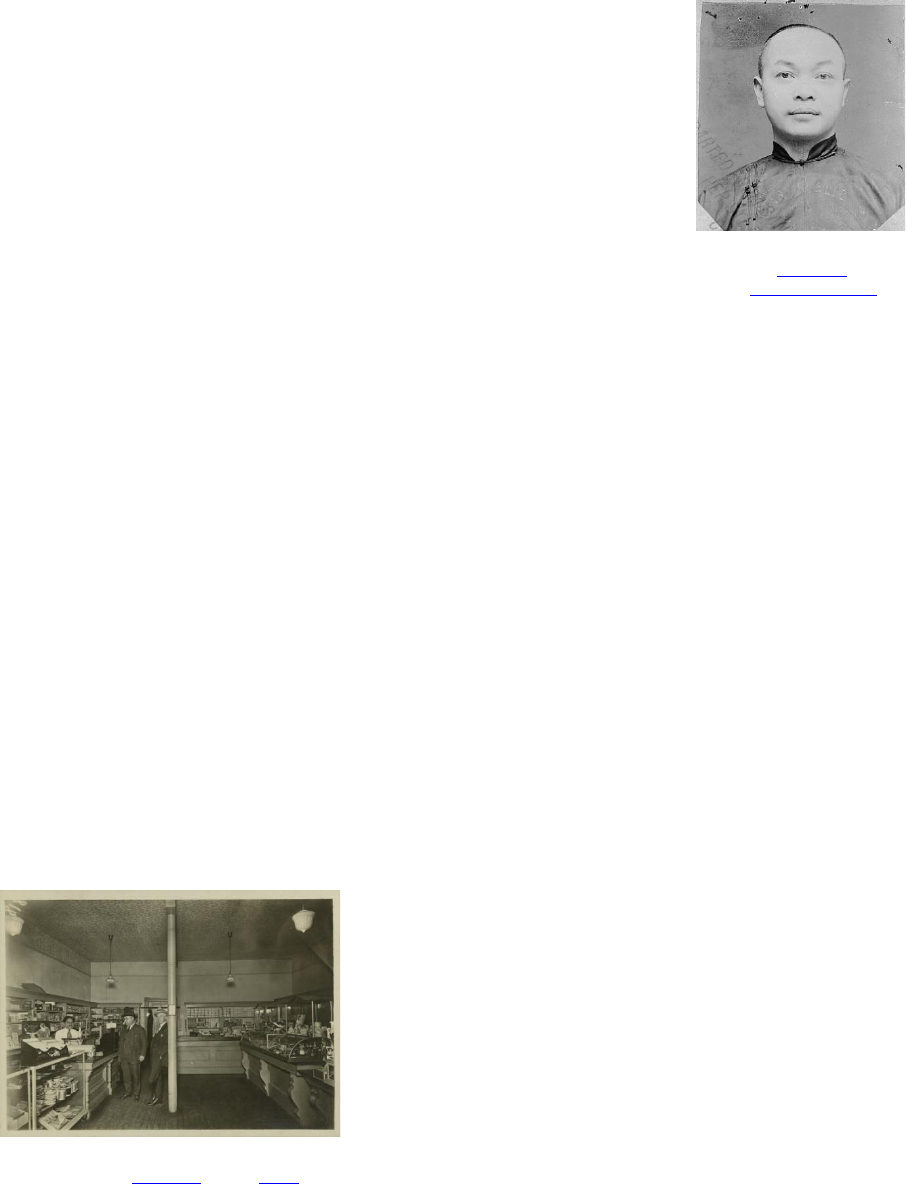

Mid 1800s to early 20

th

Century ............................................................................................................. 78

Global Conflicts & the 20

th

Century ........................................................................................................ 82

Application 5.1 Shifting Perspective: Self-Determination .................................................................. 82

Application 5.2 Shifting Perspective: Japanese Internment ............................................................... 83

New Immigrants & Expansion of Diversity .............................................................................................. 83

The Recent Past ....................................................................................................................................... 85

Biographical Reflection 5.1 Southeast Asian Refugees....................................................................... 86

Summary .................................................................................................................................................. 88

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER vi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................... 88

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................... 88

References ............................................................................................................................................... 88

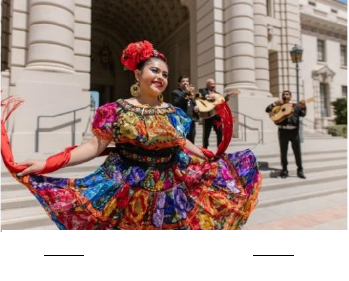

Module 6. Our Story: Latinx Americans ..................................................................................... 90

Learning Objectives ................................................................................................................................. 90

Key Terms & Concepts ............................................................................................................................. 90

Introduction ............................................................................................................................................ 90

Indigenous People’s & Colonization ....................................................................................................... 91

Westward Expansion & Warfare ............................................................................................................. 92

Labor & Civil Rights ................................................................................................................................. 96

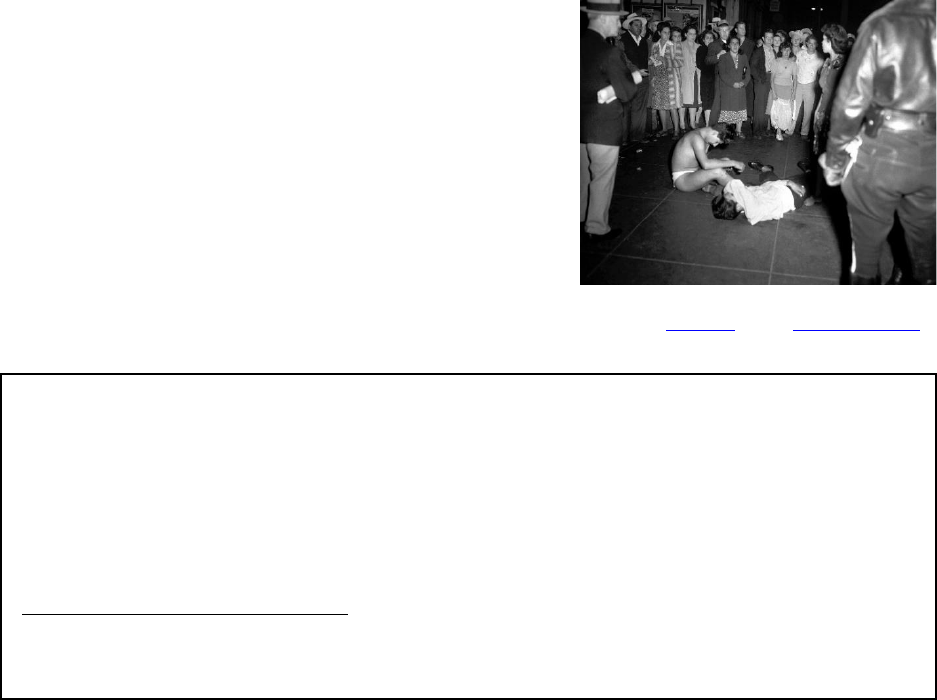

Application 6.1 Shifting Perspective: Zoot Suit Riots .......................................................................... 97

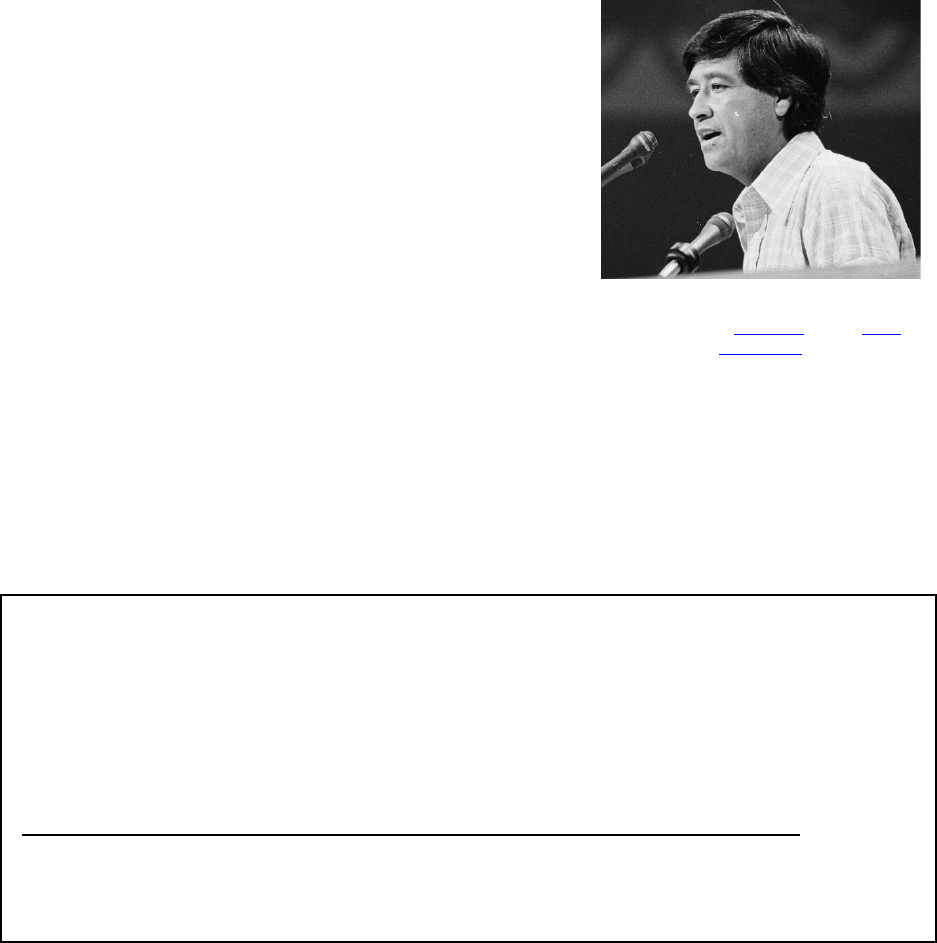

Application 6.2 Shifting Perspective: Labor & the Struggle of Migrant Farm Workers ...................... 99

The Recent Past ..................................................................................................................................... 100

Biographical Reflection 6.1 A Little Goes a Long Way ...................................................................... 101

Summary ................................................................................................................................................ 101

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................. 102

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................. 102

References ............................................................................................................................................ 102

Module 7. Our Divisions ............................................................................................................ 103

Learning Objectives ............................................................................................................................... 103

Key Terms & Concepts ........................................................................................................................... 103

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 103

Cultural Hierarchies ............................................................................................................................... 104

Prejudice ................................................................................................................................................ 104

Biographical Reflection 7.1 New Home and Race Relations ............................................................. 105

Application 7.1 The Thinking Behind Prejudice ................................................................................ 109

Biographical Reflection 7.2 This is Not an Altercation ...................................................................... 110

Application 7.2 The Affect of Implicit Bias ........................................................................................ 114

Racism & Exploitation ........................................................................................................................... 114

Application 7.3 Little Acts of Discrimination ..................................................................................... 115

Application 7.4 Recognizing White Privilege ................................................................................... 116

Summary ................................................................................................................................................ 117

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER vii

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................. 117

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................. 117

Application 7.5 Visual Ethnography Part 1 ....................................................................................... 118

Application 7.6 Visual Ethnography Part 2 ....................................................................................... 119

References ............................................................................................................................................. 119

Module 8. Our Way Forward .................................................................................................................. 123

Learning Objectives ............................................................................................................................... 123

Key Terms & Concepts ........................................................................................................................... 123

Introduction ........................................................................................................................................... 124

Racial & Social Justice ............................................................................................................................ 124

Biographical Reflection 8.1 The Blue Mornings ................................................................................ 125

Reducing Prejudice ........................................................................................................................... 128

Biographical Reflection 8.2 My Turn, Why Ending Prejudice Is Not a Hopeless Cause .................... 130

Building Community .............................................................................................................................. 132

Table 4. Anti-Racist & Anti-Colonial Practices .................................................................................. 132

Cultural Intelligence .......................................................................................................................... 132

Biographical Reflection 8.3 Religious & Cultural Conflict ................................................................. 134

Application 8.1 Cultural Intelligence Resources ............................................................................... 136

Conflict Resolution Strategies & Practices ........................................................................................ 137

Table 5. Five Modes of Resolving Conflict ........................................................................................ 138

Application 8.2 Conflict Reduction In Action .................................................................................... 139

Table 6. Conflict Reduction Techniques ........................................................................................... 140

Truth Telling & Social Discourse ....................................................................................................... 140

Table 7. Types of Ignorance .............................................................................................................. 141

Summary ................................................................................................................................................ 142

Review Questions .................................................................................................................................. 142

To My Future Self .................................................................................................................................. 142

Application 8.3Fostering Connections .............................................................................................. 143

References ............................................................................................................................................. 144

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER viii

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

PREFACE

Dear Student & Faculty Scholars,

This book is an introduction or primer to ethnic studies and is not a complete or comprehensive

review of the literature. We identified and included major concepts, theories, perspectives, and

voices in ethnic studies with research from anthropology, history, political science, psychology,

and sociology to offer an inclusive approach for critical inquiry.

The content was reviewed by our peers using the Academic Senate for California Community

Colleges Open Educational Resources Initiative Evaluation Rubric and Inclusion, Diversity,

Equity, and Anti-Racism (IDEA) Audit Framework.

The manuscript is openly licensed to offer our readers the opportunity to revise, remix,

redistribute, reuse, retain, and expand the literature to fit learning needs. We encourage you to

think about and consider your own family history, stories, and traditions as you explore and

build on this content.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER ix

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

A NOTE TO OUR READERS

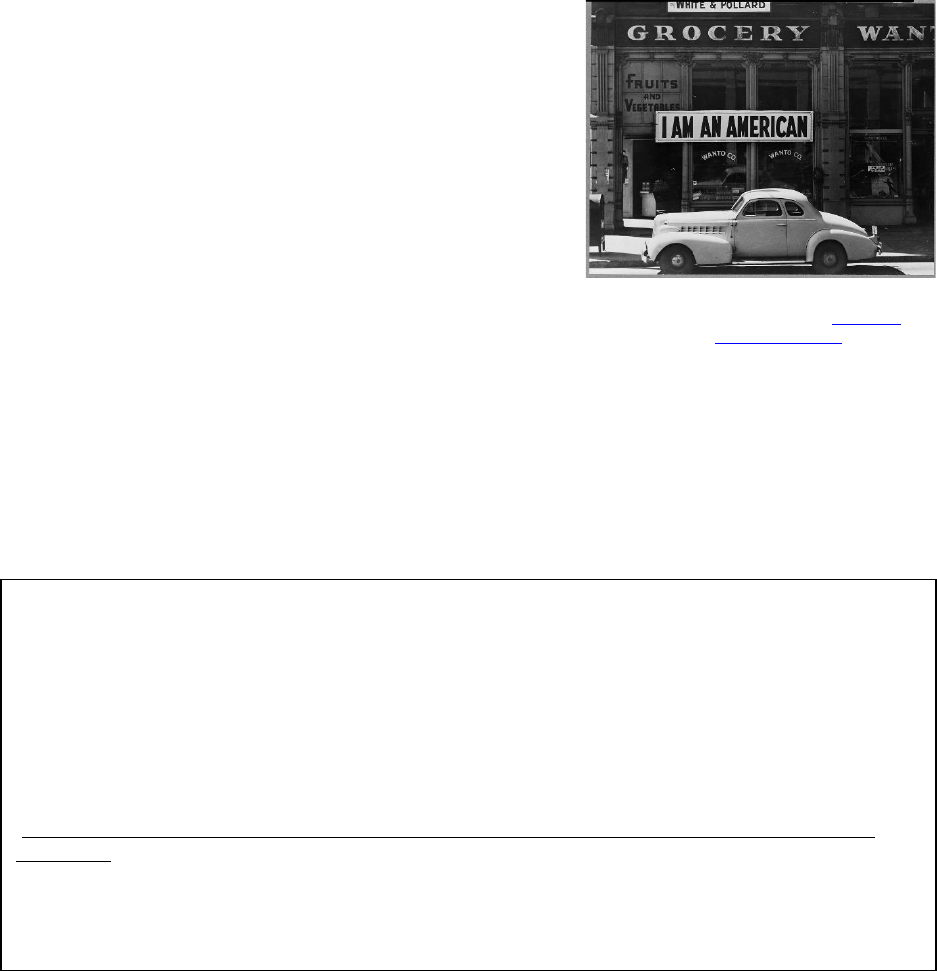

The American Dream. We are all familiar, right? Immigrants throughout our history have come

to the country with the belief that the opportunities are endless. For the founding fathers, it

was the “pursuit of property.” For John O’Sullivan it was the right “to [the] possession of the

homes conquered from the wilderness of their own labors and dangers,” and for Franklin D.

Roosevelt, it was the “Four Freedoms” – Freedom of Speech and worship, as well as freedom

from want or fear. For many immigrants and people of color, this American Dream was

farfetched and difficult to attain, but they continued to try – if not for themselves, but for their

children.

But they were met with resistance. Obstacles. Legislation. Discrimination. Hatred and violence.

Who is America? This question can seem simple at first glance, but then gradually becomes

more complicated as we contemplate our answer. Over the course of its history, the people of

America have changed drastically, diversifying extensively. Each group that has contributed to

this diversity has a story - a history that is both unique and sometimes similar to other groups in

America. The historical narrative presented here seeks to illustrate the people often overlooked

for their contributions to the nation that we call home.

The historical narrative was written under the framework of a few concepts. First, we followed

a general timeline that is covered in most U.S. history survey courses. The timeline allows the

reader to find some familiarity with the narrative that they have already learned in formative

years. This approach might also serve as a refresher for some students. Secondly, while the

traditional narrative and timeline was followed, some key events were given less attention, or

left out altogether. This was a choice made to diversify the historical narrative and expand the

perspectives of the traditional description to include Black, Brown, Asian, and Indigenous

peoples’ voices. Lastly, this is a primer in ethnic studies, and should serve as an opening to

widen one’s scope of knowledge with inclusivity and equity in mind.

Historically, some language used to label or categorize groups covered in this book has been

problematic. Labels and identity are deeply personal to most people and should be respected.

With those notions in mind, we have aligned our terminology with the generally accepted

academic terms of racial groups, along with current trends in accepted language.

The historical narrative presented in this book is meant to assert voices once unheard, voices

that believed and continue to believe in the possibilities of the American Dream, voices that

embody a fierce spirit of freedom and opportunity. Together, they have been an integral part of

the forging of this country. These are their stories.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER x

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

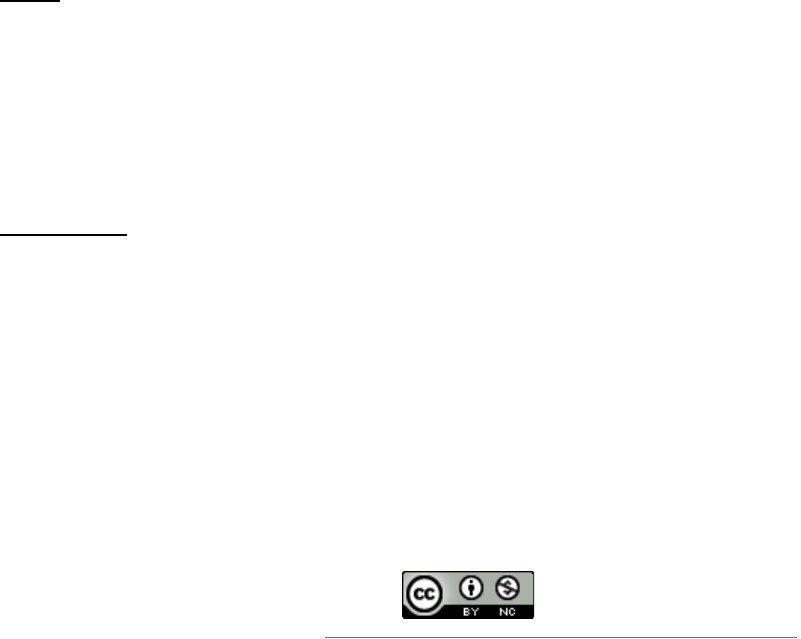

Vera Guerrero Kennedy was born and raised in San Joaquin Valley,

California. She received a B.A. in sociology (1995), M.P.A. in political

science with an emphasis in public administration (1999) from Fresno

State and a doctorate in education (Ed.D.) with an emphasis in

curriculum and instruction from Argosy University (2012).

Vera is a tenured faculty at West Hills College Lemoore and Lecturer at

Fresno State. Her publications include The Influence of Cultural Capital

on Hispanic Student College Graduation Rates (2012), Critical Thinking

about Social Problems (2017), Beyond Race: Cultural Influences on Human Social Life (2018),

and A Career in Sociology (2020). She is also faculty for the 2021-2022 American Association of

Colleges & Universities Institute on Open Educational Resources and recently completed

appointments as the Distance Education Program Coordinator & Pedagogical Coach at West

Hills College Lemoore (2020-21) and OER Fellow at Fresno State (2019).

Before teaching full-time, Vera was the Juvenile Justice Services Coordinator for the Fresno

Superior Court and assisted in the establishment facilitation of the Juvenile Mental Health Court

for Fresno County. She served on the Board of Directors for Comprehensive Youth Services, a

child abuse prevention agency, and was appointed by the Fresno County Board of Supervisors

to serve on the Fresno County Foster Care Oversight Committee for six years.

She and her husband, Greg, reside in Fresno, California with their Pomeranian, Otter.

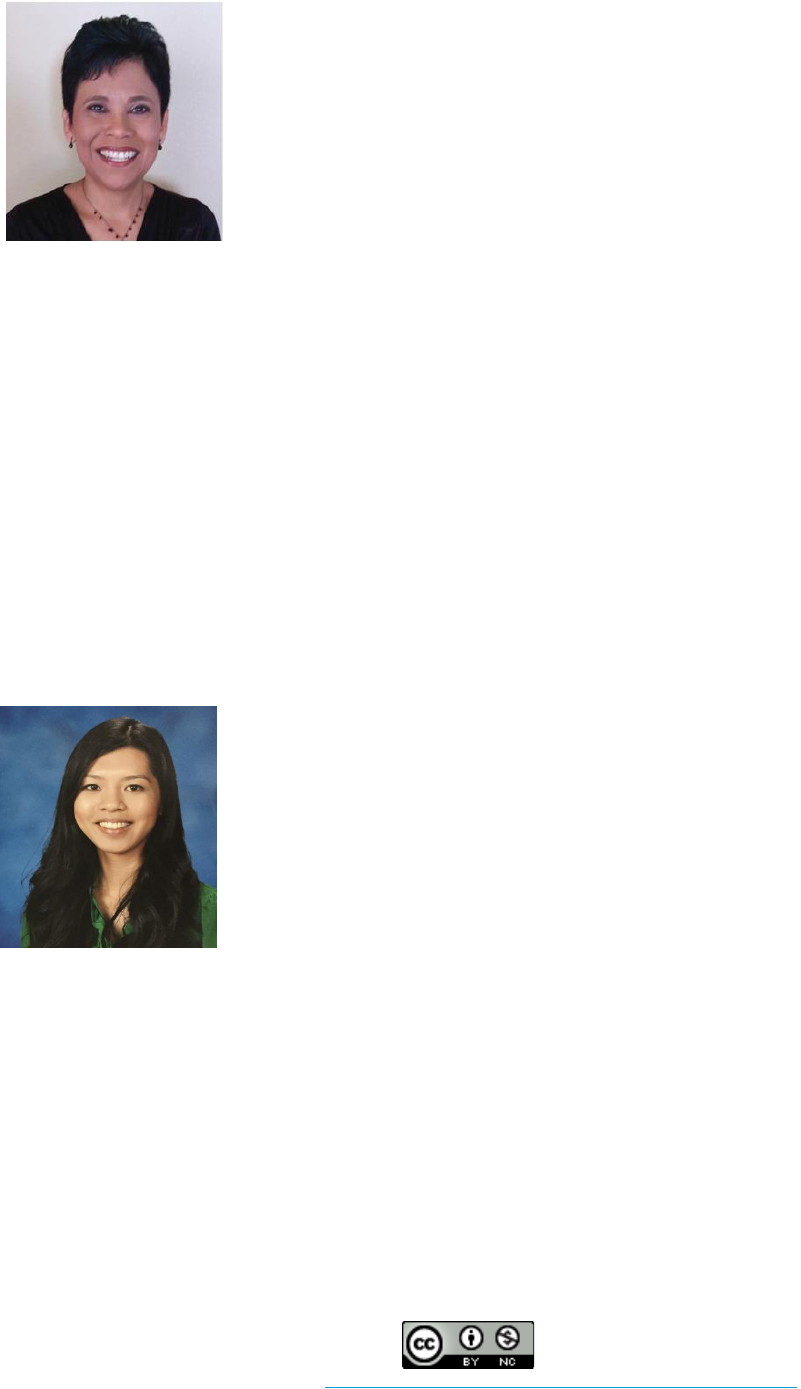

Rowena Bermio is the child of Filipino immigrants that came to

California in the early 1980s. She received her master’s degree in

history from California State University Fresno and also retains a degree

in art history. For the last six years, she has taught U.S. and world

history for Fresno State, West Hills College Lemoore, and other

community colleges in the Central Valley.

At West Hills, Rowena is an active member of the Social Justice and

Equity Task Force, aiding in efforts to enhance inclusivity and equity at

the college. She has given several lectures on culture and diversity on campus with task force

goals in mind.

Rowena currently lives and teaches in the Central Valley with her partner Margaret, and their

pets Shane, Tig, and Mad Max.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER xi

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

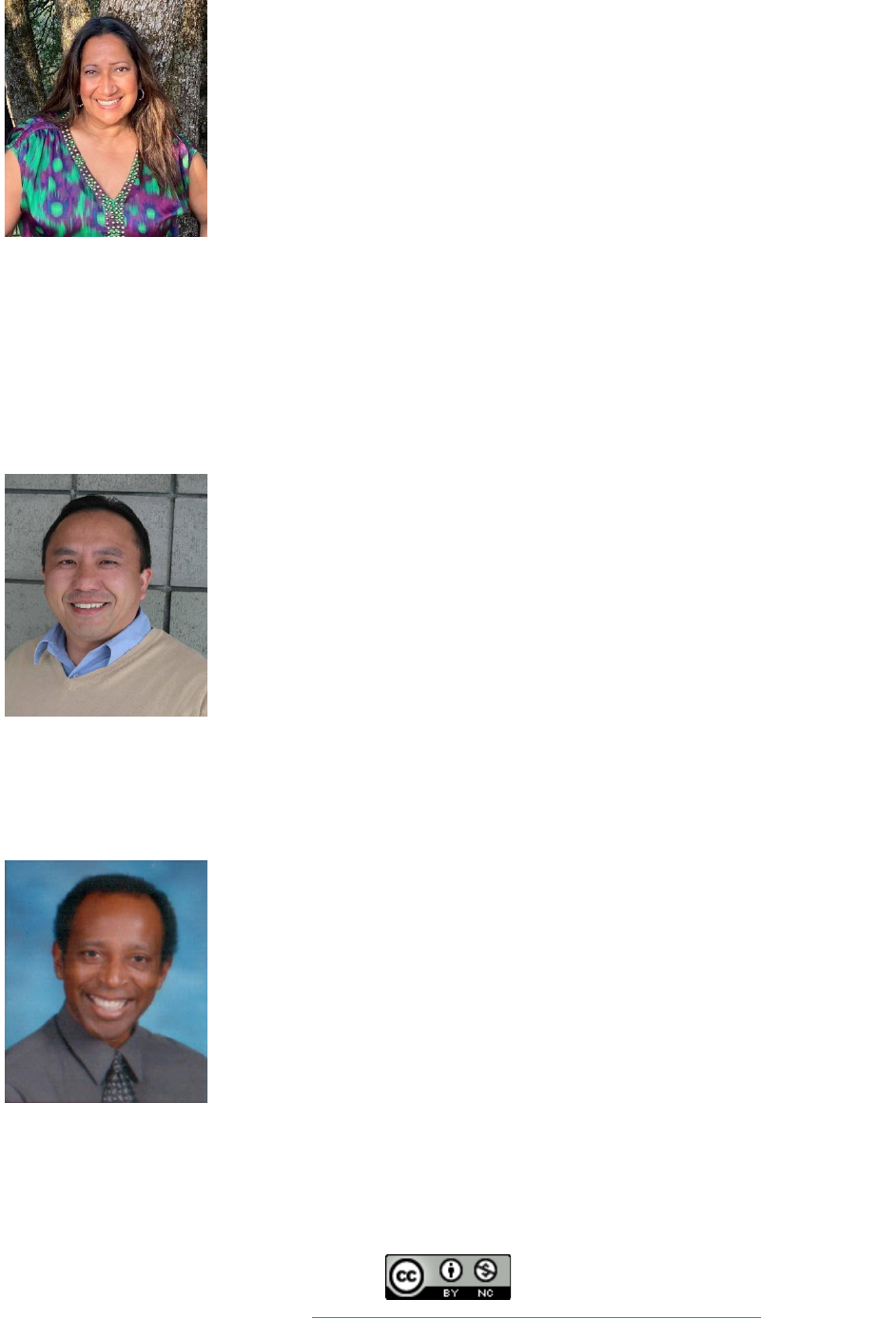

Guadalupe Capozzi is a native of the Central Valley and teaches

criminal justice at West Hills College Lemoore. She started her career as

a Correctional Officer for the California Department of Corrections,

California Correctional Facility for Women in Chowchilla, California then

promoted to a Correctional Counselor at the Substance Abuse and

Treatment Facility in Corcoran, California. In 2003 she transitioned to a

Parole Agent. Most recently, she has managed two parole units in Kings

and Tulare Counties including Coalinga State Hospital. Guadalupe

earned her B.A. in criminal justice with an emphasis on restorative

justice from Fresno Pacific University in Fresno, California. She teaches Principled Policing,

Family Systems, Staff Suicide Awareness, and Diversity in the Workplace at the Basic Parole

Agent Academy and is the assistant training coordinator for the district. She previously worked

as a Communicable Disease Consultant and Investigator with the State Department of

Health. Guadalupe serves on the board of Champions Recovery of Kings County and is a

member of the Women’s Ministry at her church. She and her four children live in Lemoore,

California.

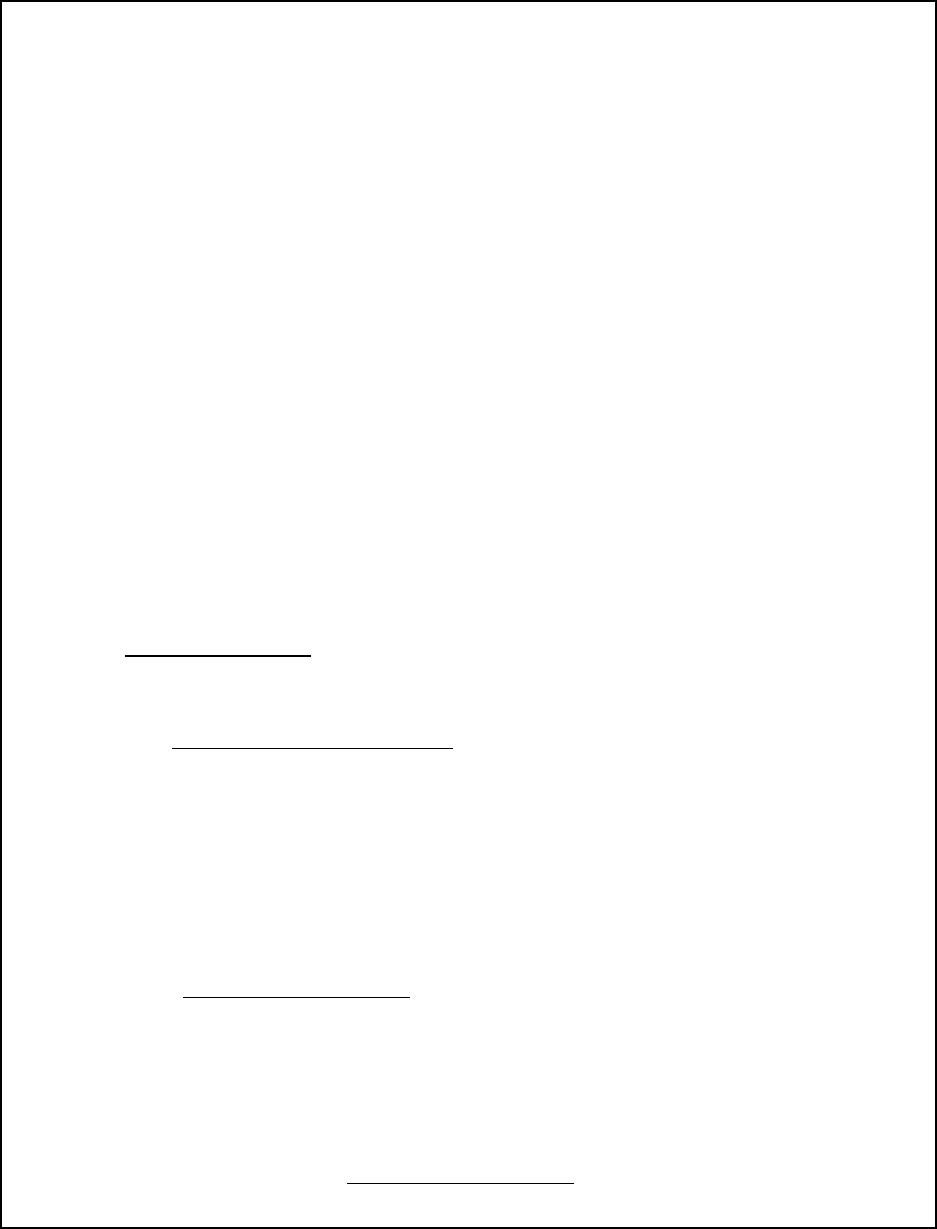

Silas Cha holds a Bachelor of Arts in philosophy from the University of

California, Berkeley and a Master of Arts in international relations from

California State University, Fresno. He teaches political science and

ethnic studies at the community college and cross-cultural job training

and business ethics at Fresno Center for New Americans, a non-profit

organization. While serving as the associate director of the non-profit

organization, Silas conducted research on Hmong, Lao, Cambodian, and

Vietnamese resettlement patterns in the Central Valley as related to

education, social and race relations, health, housing, and economic

development. In addition, Silas served as an advisory member for Valley Health Policy Institute

at Fresno State and The Fresno Bee, where he published monthly articles as a guest columnist.

Many of the issues in his columns were on cross-cultural nuances, race relations, religious and

medical conflicts, and social justice. He is married to a wonderful wife and has two daughters.

Daryl Johnson has a master’s degree in public administration and

human resources from Gate University, San Francisco, California. He

also holds an M.A. in education from Fresno Pacific University, Fresno,

California. He grew up in Washington State and received his

undergraduate degree in communications from the University of

Washington in Seattle and possesses California state certifications as a

teacher performance assessor, ESL instructor, and community college

speech instructor. He currently serves as Lead Instructor for the Fresno

Pacific University Teacher Preparation Program and is a

communications instructor at West Hills College Lemoore. Mr. Johnson is a former USAF officer

and civil servant, with service in Korea, Germany, and stateside. He designed the compensatory

education program for NATO Base Geilenkerchen, Germany’s military dependent children, and

worked for NATO as an ELD instructor. He and his family currently live in Hanford, California.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 1

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.

MODULE 1. THE SIGNIFICANCE OF ETHNIC STUDIES

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

At the end of the module, students will be able to:

1. understand the difference between race and ethnicity

2. discuss the social construction of race

3. explain racial framing

4. compare intergroup relations in terms of racial-ethnic group conflict and tolerance

5. assess systemic racism and structural explanations for racial and ethnic inequality

6. evaluate the intersectionality of race, ethnicity and other social categories on systems of

oppression

7. provide examples of racial-ethnic stratification and inequality

8. define majority (dominant) and minority groups (subordinate)

9. interpret social indicators and data on racial and ethnic inequality in the United States

KEY TERMS & CONCEPTS

Achieved Status

Ascribed Status

Competition

Dominant Group

Double Consciousness

Egocentric

Ethnicity

Ethnocentrism

Fluid Competitive Race Relations

Genocide

Internal Colonialism

Intersectionality

Labels

Macro-level

Micro-level

Minority Groups

Multiculturalism

Otherness

Paternalistic Pattern

Patterns of Intergroup Relations

Pluralism

Population Transfer

Race

Racial Disparities and Inequality

Racial Formation

Rigid Competitive Pattern

Segregation

Social Status

Sociocentrism

Status Shifting

Stratification

Subordinate Group

Systemic Racism

Unequal Power

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 2

INTRODUCTION

Have you ever had your experience or story misrepresented or retold in an inaccurate way?

Has anyone ever taken something of value from you without asking or providing

compensation?

The feelings and thoughts you hold about these questions are not different from other people

in the United States, particularly those who were forcible driven from their homeland,

smuggled into this country from another place, stripped of their identity, exploited for their

resources and labor, or those who have been killed or murdered for being different. The most

disturbing part of our history and the characterization of these incidences is the ongoing denial,

recognition, and reparations for the people who today remain inflicted by the

misrepresentation and injustice of our social structures, institutions, and ideologies. No one

likes their history or experience retold through fallacies, stereotypes, or lies. No one likes their

life or way of living taken from them involuntarily.

Technology and social media have made it easy to block out and change what we hear and

think about each other, our experiences, and our stories. Ironically, these tools have also made

it easier to share our lives and bring others into our world without time or borders.

Why is it important to share your experience or tell your story in an honest and accurate way?

What is the value in sharing your experience or story?

By telling our stories and sharing our experiences, we acknowledge our existence and

humanity. Because we have not retold or allowed some people to share their stories and

experiences, we deprive them of this acknowledgement. We make some people less than

human and justify it by keeping truths and facts hidden.

This book examines race and ethnicity as understood through our history and the experiences

of major underrepresented racial groups including African Americans, Asian Americans, Latinx

Americans, and Native Americans in the United States. We will explore a broad range of

sociocultural, intellectual, and historical experiences that form the construction and

intersectionality of race and ethnicity in the United States by applying macro and micro

perspectives of analysis. Furthermore, we will examine the cultural and political contexts

behind the systems of power, privilege, and inequality impacting Americans of color. Emphasis

is placed on racial and social justice with methods for building a just and equitable society.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 3

APPLICATION 1.1

ACKNOWLEDGING INDIGENOUS PEOPLE’S LAND

Goal

To illustrate and compose a method for acknowledging Indigenous people’s land to recognize its connection to

our lives and country.

Instructions

1. Honor Native Land

Acknowledgement is a simple, powerful way of showing respect and a step toward correcting the stories and

practices that erase Indigenous people's history and culture by inviting and honoring the truth. Naming is an

exercise in power. Who gets the right to name or be named? Whose stories are honored in name? Whose are

erased? Acknowledgement of traditional land is a public statement by naming the traditional Native

inhabitants of a place. It honors their historic relationship with the land.

We are introducing the practice of land acknowledgment to create greater public consciousness of Native

sovereignty and cultural rights, a step toward equitable relationship and reconciliation. Join us in adopting,

calling for, and spreading this practice. To participate in this activity, take a moment to research and identify

the traditional inhabitants of the land you are on today.

Here are some resources you may view online:

Wikipedia - Entries on many cities document some history of Indigenous inhabitation. Cross-check what you

find to verify accuracy.

Native Land (https://native-land.ca/) - The website provides educational resources to correct the way that

people speak about colonialism and indigeneity, and to encourage territory awareness in everyday speech and

action.

Native Languages (http://www.native-languages.org/) - The resource offers a breakdown by state, with

contact information for local tribes.

2. Amplify Your Acknowledgement

Take a moment to acknowledge the traditional inhabitants of the land you are on today. Post an image or story

about this class activity on social media where your acknowledgement was offered and tag it

#HonorNativeLand to inspire others.

3. Honor Native Land Guide

#HonorNativeLand (https://usdac.us/nativeland)

This resource provides individuals and organizations a guide on how to open public events and gatherings with

acknowledgment of the traditional Native inhabitants of the land.

4. Develop Your Acknowledgement

Formulate a statement of acknowledgment you may share at the beginning of class meetings, campus events,

or public gatherings. Craft yours after considering several levels of detail you might introduce as illustrated on

page 6 of the Honor Native Land Guide (https://usdac.us/nativeland). Be prepared to share your

acknowledgment with other scholars in class meetings.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 4

UNDERSTANDING RACE

There are two myths or ideas about race. The first suggests people inherit physical

characteristics distinguishing race. The second insinuates that one race is superior to others or

that one “pure” race exists.

Scientific research mapping of the human genome system found that humans are homogenous

(Henslin, 2011). Race is truly an arbitrary label that has become part of society’s culture with no

justifiable evidence to support differences

in physical appearance to substantiate the

idea that there are a variety of human

species. Scientific data finds only one

human species making up only one human

race. Evidence shows physical differences in

human appearance including skin color are

a result of human migration patterns and

adaptions to the environment (Jablonski,

2012). These data underline the fact that

the concept of race is socially constructed.

Society chooses to define the basis and classification of physical characteristics. Racial terms

classify and stratify people by appearance and inherently assign individuals and groups as

inferior or superior in society based on their physical traits (Kottak & Kozaitis, 2012). This

classification and social status of race and racial groups change over time and varies from one

society to another as viewpoints, perspectives, and knowledge adapts and evolves. People use

physical characteristics to identify, relate, and interact with one another.

APPLICATION 1.2

BREAKING THE ILLUSION OF SKIN COLOR

Goal

To understand the influence of the atmosphere, environment, and adaptation on skin color.

Instructions

Watch the TED-Ed video Breaking the Illusion of Skin Color presented by Nina Jablonski

(https://ed.ted.com/lessons/nina-jablonski-breaks-the-illusion-of-skin-color). Answer the following questions

about skin color and adaptation:

1. Why does Dr. Jablonski study NASA satellite data?

2. Why and how did lightly pigmented skin develop?

3. What are the potential health problems for darkly pigmented people living in low-UV areas of the

world?

4. According to Dr. Jablonski, where did Charles Darwin go wrong?

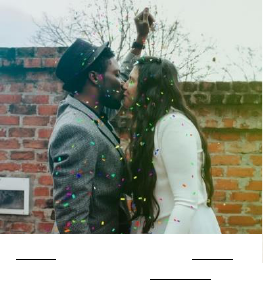

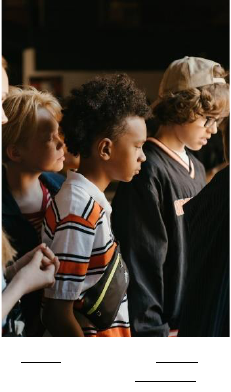

Image by Monstera, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 5

In this book, we will discuss and use the terms race and racial group interchangeably. Even

though the concept of race is not biologically sound, people do identify with the term and are

often grouped based on the socially constructed concept of race. In reality, race and racial

group classification influences people’s life experiences and choices (Farley, 2010; Winant,

1994; Taylor, 1998; Duster, 2001).

The social process of recognizing and defining racial characteristics,

labels, and groups is known as racial formation (Omi & Winant,

1994). This process solidifies how race is understood and is

propelled by political interests. The results directly impact the

social and political consequences of people’s lives, and it is the

primary reason society recognizes race as an important

classification and why its definition and meaning transform over

time (Farley, 2010). Powerful and influential people use race to

create divisions or bring people together, whichever serves their

interests.

Ethnicity refers to the cultural characteristics related to ancestry

and heritage. Ethnicity describes shared culture such as group

practices, values, and beliefs recognized by people in and the group

itself (Griffiths et al., 2015). People who identify with an ethnic

group share common cultural characteristics (i.e., nationality, history, language, religion, etc.).

Ethnic groups select rituals, customs, ceremonies, and other traditions to help preserve shared

heritage (Kottak & Kozaitis, 2012).

Lifestyle and other identity characteristics such as geography and region influence how we

adapt our ethnic behaviors to fit the context, environment, or setting in which we live. Culture

is also central in determining how humans grow and develop including diet, food preferences,

and cultural traditions promoting physical activities, abilities, well-being, and sport (Kottak &

Kozaitis, 2012). A college professor of Mexican decent living in Central California will project

different behaviors than someone of the same ethnic culture who is a housekeeper in Las

Vegas, Nevada. Differences in profession, social class, and region will influence each person’s

lifestyle, physical composition, and health though both may identify and affiliate themselves as

Mexican.

The ethnicity of parents largely determines the ethnicity of offspring through socialization.

Ethnicity is a social characteristic, like race, that is passed from generation to generation

(Farley, 2010). For example, the California natives of the San Joaquin Valley known as Yokuts,

meaning people, were divided into true tribes each with their own name, language, and

territory (Tachi Yokut Tribe, 2021). Learning cultural traits and characteristics are important for

developing identity and ethnic group acceptance. Cultural socialization occurs throughout one’s

life course.

Image by Thiago Miranda, Pexels

is licensed under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 6

Not all people see themselves as belonging to an ethnic group or view ethnic heritage as

important to their identity. People who do not identify with an ethnic group either have no

distinct cultural background because their ancestors come from a variety of cultural groups and

offspring have not maintained a specific culture, instead have a blended culture, or they lack

awareness about their ethnic heritage completely (Kottak & Kozaitis, 2012). It may be difficult

for some people to feel a sense of solidarity or association with any specific ethnic group

because they do not know where their cultural practices originated and how their cultural

behaviors adapted over time.

What is your ethnicity? Is your ethnic heritage very important, somewhat important, or not

important in defining who you are? Why?

RACE-ETHNIC RELATIONS TODAY

At present, people of color are now more than 80% of the world’s population and becoming the

demographic majority (Feagin, 2014). The U.S. population is more diverse than ever in its

history, and it is projected that by the year of 2040 Whites will become the statistical minority

in the United States. With these demographic changes, Americans of color will become more

influential in politics, economics, and increase societal pressure to them with greater equity and

justice.

Intergroup relations between racial-ethnic groups

are complex. Because racial-ethnic group creation

is politically motivated, people of color often

experience frustration, anger, and trauma from

ongoing conflict, discrimination, and inequality

(Farley, 2010). Our race and ethnic heritage shapes

us in many ways and fills us with pride, but it is

also a source of conflict, prejudice, and hatred.

There are seven distinct patterns of intergroup

relations between majority (powerful) and

minority (subordinate) groups influencing not only

the racial and ethnic identity of people but also the opportunities and barriers each will

experience through social interactions. Maladaptive contacts and exchanges include genocide,

population transfer, internal colonialism, and segregation. Genocide attempts to destroy a

group of people because of their race or ethnicity. “Labeling the targeted group as inferior or

even less than fully human facilitates genocide” (Henslin, 2011, p. 225). Population transfer

moves or expels a minority group through direct or indirect transfer. Indirect transfer forces

people to leave by making living conditions unbearable, whereas direct transfer literally expels

minorities by force.

Another form of rejection by the dominant group is a type of colonialism. Internal colonialism

refers to a country’s powerful dominant group exploiting the low-status, minority group for

Image by Saroj Gajurel, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 7

economic advantage. Internal colonialism generally accompanies segregation (Henslin, 2011). In

segregation, minority groups live physically separate from the dominant group by law.

Three adaptive intergroup relations include assimilation, multiculturalism, and pluralism. The

pattern of assimilation is the process by which a minority or less powerful group assumes the

attitudes and language of the dominant or mainstream culture. An individual or group gives up

its identity by taking on the characteristics of the dominant culture (Griffiths et al., 2015). For

example, the original language, cultures, and family ties of African Americans were destroyed

through slavery, and any wealth or resources gained since have been challenged or taken

through White-on-Black oppression. When minorities assimilate by force to dominant

ideologies and practices, they can no longer practice their own religion, speak their own

language, or follow their own customs. In permissible assimilation, minority, low-status groups

adopt the dominant culture in their own way and at their own speed (Henslin, 2011).

Multiculturalism is the most accepting intergroup

relationship between the powerful dominant and

subordinate minority. Multiculturalism or pluralism

encourages variation and diversity. Multiculturalism

promotes affirmation and practice of ethnic

traditions while socializing individuals into the

dominant culture (Kottak & Kozaitis, 2012). This

model works well in diverse societies comprised of a

variety of cultural groups and a political system

supporting freedom of expression. Pluralism is a

mixture of cultures where each retains its own

identity (Griffiths et al., 2015). Under pluralism, groups exist separately and equally while

working together such as through economic interdependence where each group fills a different

societal niche then exchanges activities or services for the sustainability and survival of all. Both

the multicultural and pluralism models stress interactions and contributions to their society by

all ethnic groups.

Intergroup conflict has many social and political consequences affecting the life of every

American (Farley, 2010). The most unsettling aspect is the inability or unwillingness of Whites

to see and understand the racist reality in the United States. Many Whites continue to deny

histories of racism, believe racism is a thing of the past, and do not acknowledge contemporary

racial framing and discrimination (Feagin, 2014). Whites perpetuate the ideology of “intergroup

conflict and relations” to establish the perception that all racial groups have equal impact or

resources. This corroborates an image of a level playing field among all racial groups rather

than the reality of a White-dominated and controlled systemic structure. To give an example,

for over four centuries African Americans have been subordinated and exploited for their labor.

Racial oppression has reinforced anti-Black practices, political-economic power of Whites, racial

and economic inequality, and racial framing to legitimize White privilege and power in

economic, political, legal, educational, and other institutions (Feagin, 2014).

Image by Ron Lach, Pexels is licensed under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 8

People of color experience the social world differently from Whites. The life chances and

opportunities for Americans of color are restricted in many ways, such as, who they can marry,

where they can live, what they wear or eat, who is a member of their school’s student body,

what curriculum and instruction they receive, what jobs or careers they can obtain, how they

pray, who they pray to, who represents their political interests, and what, if any, healthcare

they receive (Feagin, 2014). The institutions and services that are readily available to Whites are

not the same or always accessible for Americans of color. The few opportunities gained by

some people of color because of circumstance or chance, does not mitigate the inequities and

injustice most Americans of color live and experience. The White majority speaks about

equality but does not practice it across racial groups. Unaddressed inequities result in

continued turmoil between the majority and minority groups in the United States.

RACE-ETHNIC GROUP PERCEPTIONS

All Americans are indoctrinated in the patriotic principles of our nation’s history and the

ideologies of equality and freedom; however, these ideologies as defined by the founding

fathers and the United States Constitution are largely free of critical examination or criticism

(Parenti, 2006). Racial framing people of color dates back to our early history of colonialism and

slavery which established the foundation for White-dominated policies and institutions that

today continue to legitimize and encourage racists practices. In the United States, racist

APPLICATION 1.3

LEADERSHIP THROUGH INTERGROUP DIALOGUE

Goal

To recognize the skills needed to successfully lead or be part of a diverse team.

Instructions

1. Listen to perspectives on intergroup dialogue from students at Syracuse University

(https://youtu.be/TZaoRNsNDJI).

2. Review quotes from “Bridging Differences Through Dialogue” by Ximena Zúñiga.

• “Intergroup dialogue is face-to-face facilitated conversation between members of two or more social

identity groups that strives to create new levels of understanding, relating, and action.”

• “Intergroup dialogue encourages direct encounters and exchange about contentious issues, especially

those associated with issues of social identity and social stratification” (the hierarchy or division of

society based on status, rank, or class).

• “Dialogue that build dispositions and skills for developing and maintain relationships across

differences and for taking action for equity and social justice.”

3. Read the following article:

Nagada, B. (Ratnesh) A. (2019). Intergroup dialogue: Engaging difference for social change leadership

development. New Directions for Student Leadership, 2019(163), 29-46.

4. Identify and create a list of skills someone can develop by facilitating and participating in intergroup

dialogue.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 9

thought, sentiments, and actions are structured into everyday life such that large portions of

the White population do not view racists words, imagery, or commentary as serious (Feagin,

2014). Racial framing is concrete and advantageous for Whites, while it constructs obstacles

and is painful for Americans of color. Everyone is directly and indirectly impacted by racial

framing.

Systemic racism in our institutions by its very definition creates and maintains racial

oppression. In the United States, systemic racism is the “culture.” The policies and norms

created by the racist system is socially reproduced like any other form of culture. What

Americans call collective culture is selective transmission of elite-dominated values (Parenti,

2006). We are socialized to understand and maintain the ideologies of our ancestors even if we

are the racial-oppressed or the racial oppressors (Feagin, 2014). The culture is embedded in our

systems we live in (e.g., economy, politics, education, religion, family, etc.) so it becomes

unconscious in our everyday lives and practices. Not everyone is aware of or sees racism

because it is a social norm.

This systemic structure of racism embodies other forms of societal differences and establishes

norms within those social categories as well. This includes formal and informal norms around

(dis)ability, age, gender, sexuality, social class, among others. These categories are

interconnected and apply to individual and group systems of disadvantage and discrimination.

The intersectionality of social categorizations creates overlapping and interdependent systems

of oppression. For example, the social markers of “Black” and “female” do not exist

independently in one’s life experience. It is the intersection of these categories that influences

the life’s opportunities or challenges, such as Black women earning $0.62 for every $1.00 by

men of all races (Center for American Progress, 2018; U.S. Census Bureau of Labor Statistics,

2019).

The ongoing denial of systemic racism has resulted in

racial disparities and inequality among Americans of

color including voter discrimination, racial profiling and

police brutality, school segregation, housing

discrimination, inequity and intolerance in college and

professional sports, discrimination against faculty and

administrators in higher education, and pro-White

favoritism in top-level employment sectors and boards

of directors (Feagin, 2014). The denial of racism stems

from the ideologies of our founding fathers designed

during the 1787 Constitutional Convention. Many

convention delegates of the time were anti-democratic in their thinking fearing the “masses.”

At least 40% of the delegation were slaveowners and many others were merchants, shippers,

lawyers, and bankers who profited from commerce in slave-produced products or supplies

(Feagin, 2014). The founding fathers were aware of how they profited from slavery, and despite

this understanding would describe their own sociopolitical condition with England as “slavery

by taxation without consent.” To this end, the Constitutional Convention built a new nation to

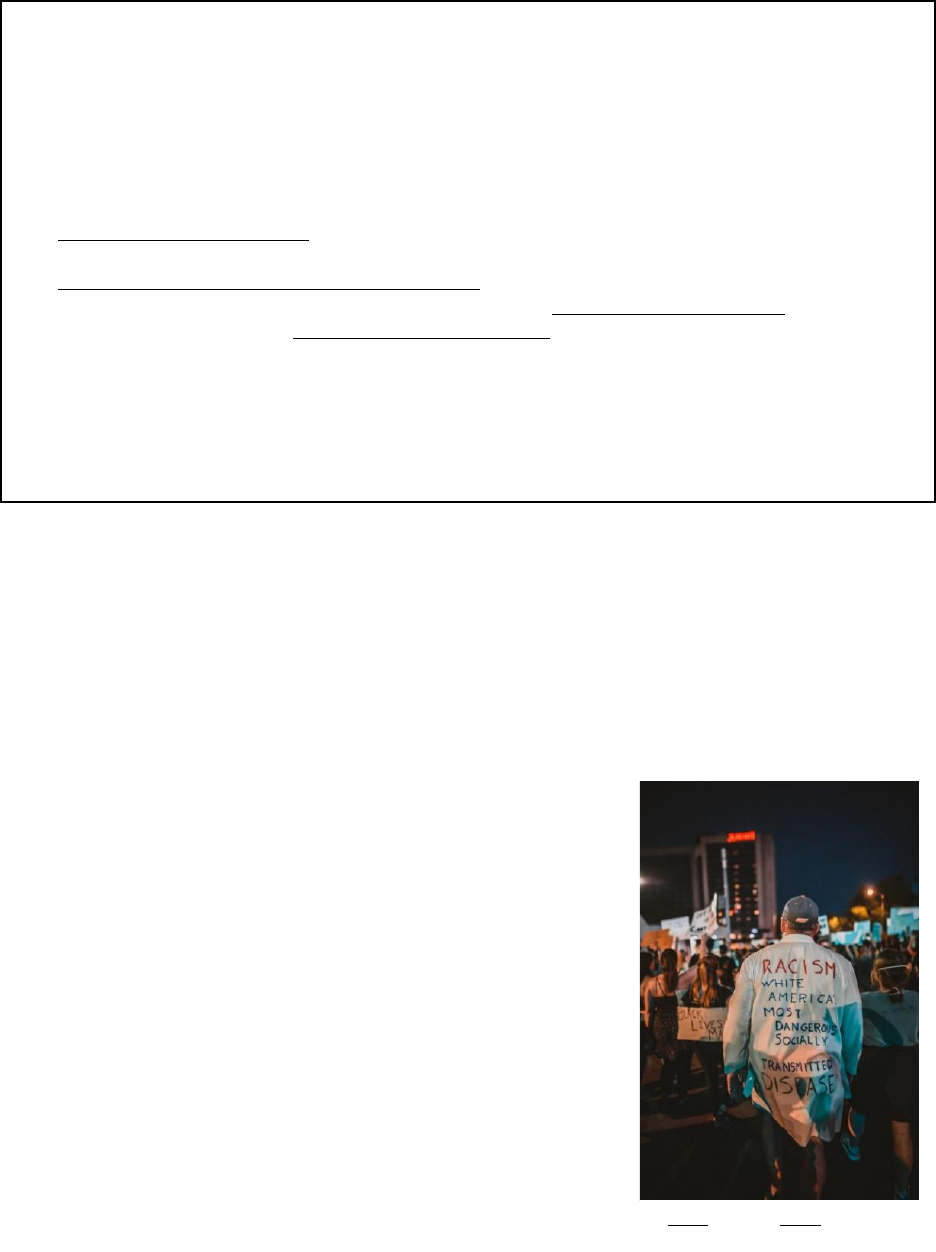

Image by Mathias P.R. Reding, Pexels is licensed

under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 10

protect the wealth of our founding fathers and those like them by defining rights using social

labels and categories such as Americans from Africa as “slaves by natural law,” indigenous

peoples as “separate nations,” or altogether excluding people, like women, by directly avoiding

inclusion. These policies and ideologies have become the foundation of American tradition.

The creation of a national racial order established at the Constitutional convention has ensued

severe consequences for centuries and yet remains the United States moral foundation. At no

point has a new Constitution or convention been held by representatives of all people to delete

the original text of racist provisions or eradicate the institutions that continue to hold

Americans of color in bondage (Douglas, 1881; DuBois, 1920; Feagin, 2014). The Constitution

created and maintained racial separation and oppression that has ensured White, elite men

would rule for centuries. Ordinary and poor Whites, even today, accept racialized order

because a White ruling class benefits White Americans and creates a positive image of

Whiteness.

Most recently, social scientists, analysts, and a new generation of Americans have argued that

there has been little attention on the racial histories, policies, and discrimination of people of

color in the United States (Feagin, 2014). There have been a variety of amendments and

resolutions by the U.S. government to acknowledge the racial injustice of our past such as the

2009 non-binding apology on the injustice of slavery and Jim Crow laws. However, these acts do

not provide real commitments or congressional actions to address the long-term impacts of

racial oppression or reduce contemporary racial discrimination (Feagin, 2014).

Considering the recent, high-profile incidents of police violence

against African Americans, what is the likelihood of racial change in

the United States? Will contemporary racial issues and social

awareness change the way Americans think? According to a Pew

Research Center survey by Horowitz, Parker, Brown, and Cox (2020),

approximately 76% of Americans note a major or minor change in

the way they think about race and racial inequality, but only 51%

believe there will be major policy changes to address racial

inequality. Results from the same survey found African Americans

(86%), Asian Americans (56%), Latinx Americans (57%), and Whites

(39%) believe when it comes to giving Black people equal rights with

White people, our country has not gone far enough. Approximately

48% of these respondents say more people participating in training

on diversity and inclusion would do a lot to reduce inequality.

EXPLANATIONS OF RACIAL INEQUALITIES

Social scientists use theories to study people. Theories help us examine and understand society

including the social structure and social value people create and sustain to fulfill human needs.

Theories provide an objective framework of analysis and evaluation for understanding the

social structure including the construction of the cultural ideologies, values, and norms and

Image by RF._.studio, Pexels is

licensed under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 11

their influence on thinking and behavior. Macro-level analysis studies large-scale social

arrangements or constructs in the social world. The macro perspective examines how groups,

organizations, networks, processes, and systems influences thoughts and actions of individuals

and groups (Kennedy, Norwood, & Jendian, 2017). Micro-level analysis studies the social

interactions of individuals and groups. The micro perspective observes how thinking and

behavior influences the social world such as groups, organizations, networks, processes, and

systems (Kennedy et al., 2017).

To understand the inequities in power and resources between racial-ethnic groups, we must

understand the social, political, and economic structure of society. A macro-level perspective

helps us understand the effect the social structure has on our life chances, opportunities, and

challenges. Whereas a micro-level perspective focuses on interpreting individual or personal

viewpoints and influences. Using only a micro-level perspective to understand racial-ethnic

inequality leads to an unclear understanding of the world from singular bias perceptions and

assumptions about people, social groups, and society (Carl, 2013). To study race and ethnic

relations and inequality, we must analyze groups and societies not simple individuals.

Race and ethnic identity influence social status or position in society. Social status serves as a

method for building and maintaining boundaries among and between people and groups.

Status dictates social inclusion or exclusion resulting in stratification or hierarchy whereby a

person’s position in society regulates their social participation by others. Racial-ethnic

inequality is a circumstance of stratification where inequality is based on race and ethnic

composition of the individual or group.

There are several structural factors that shape social stratification and intergroup relations in

society. According to Farley (2010), there are seven characteristics of a society that effect

majority-minority relations. The major influences include economics, politics, institutions, social

and cultural characteristics, and history.

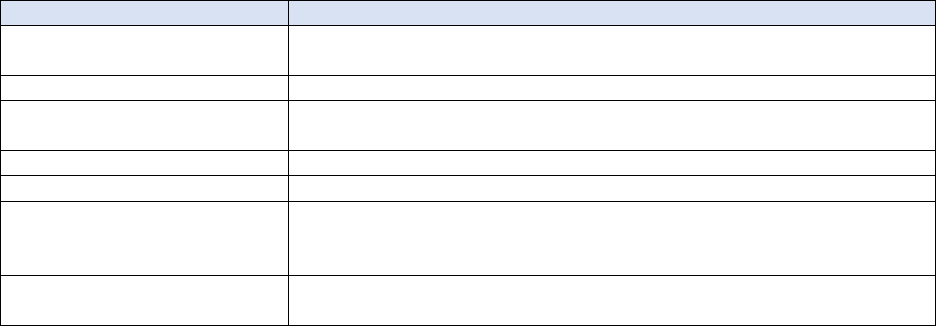

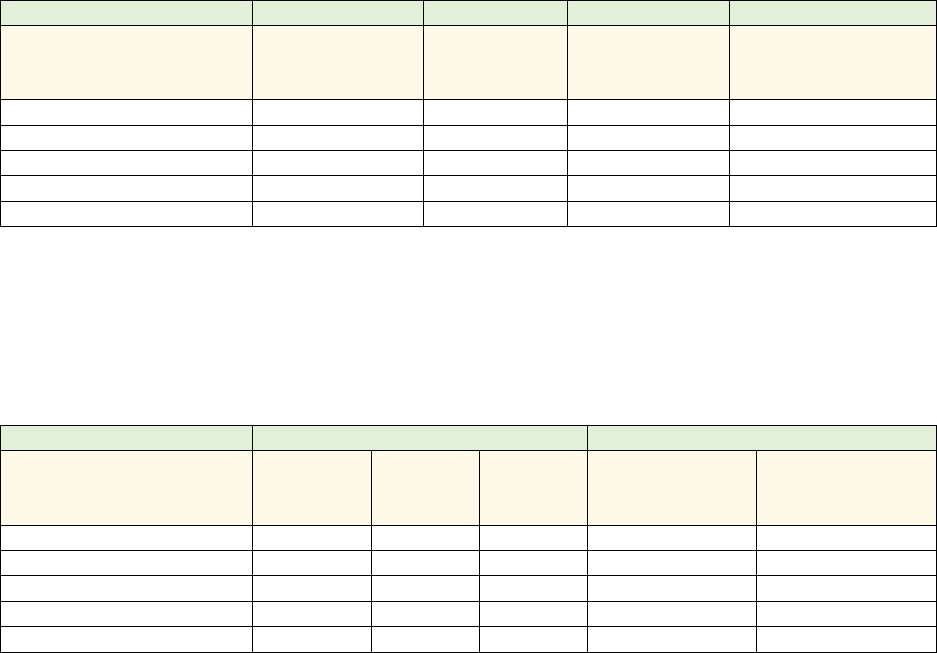

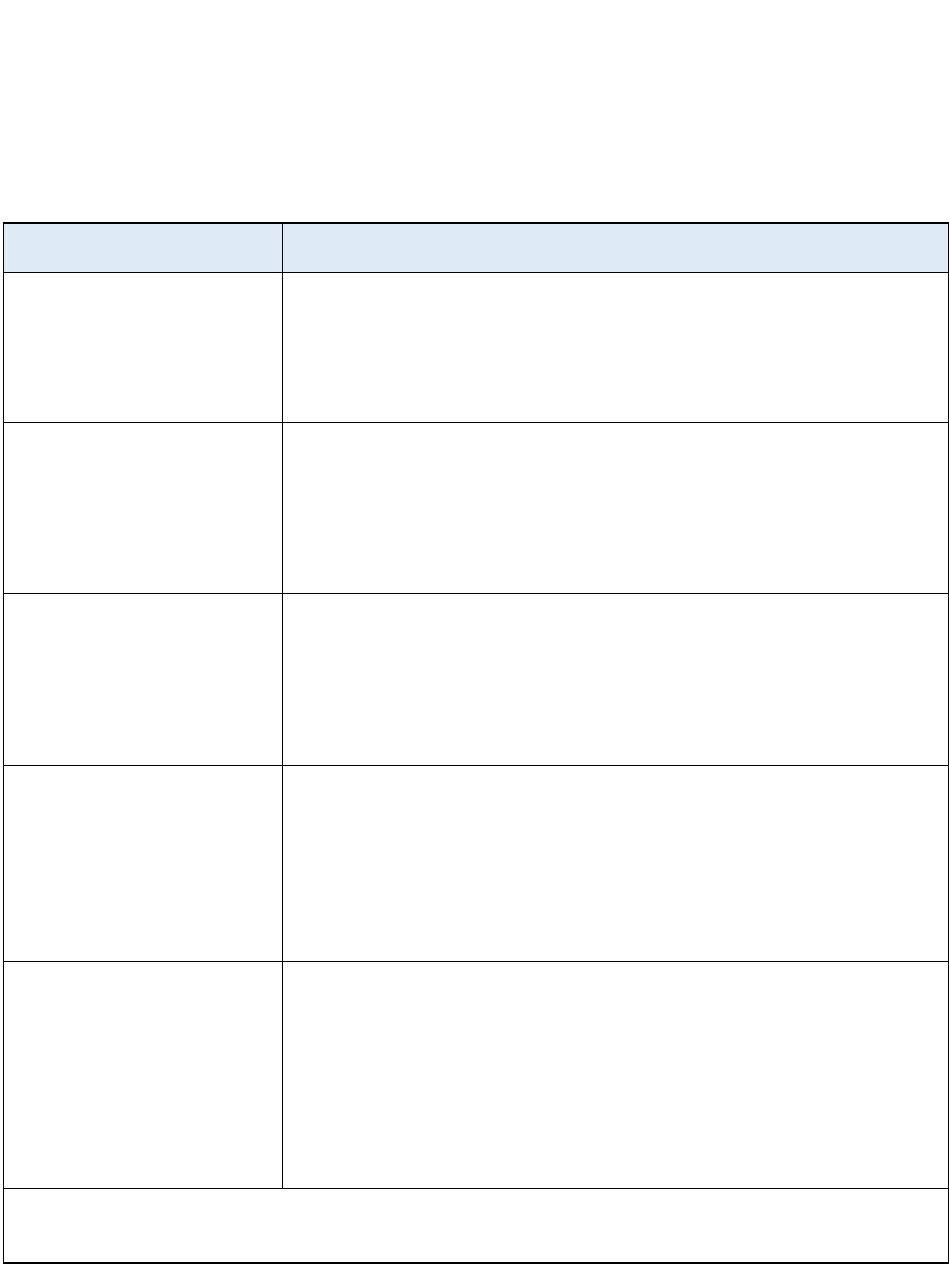

Table 1. Structural Factors of Social Position and Intergroup Relations

Structural Factor

Description

Economic System

Type of economy (i.e., capitalist, feudal, socialist, etc.) including methods of

income and wealth distribution

Economic Production

Labor, capital, goods and services to create and distribute products

Political System

Type of politic structure, power relationships between groups, and degree of

political freedom

Fundamental Institutions

Characteristics of major institutions including family, education, and religion

Dominant Culture

Controlling and imposed ideologies and value system

Cultural & Social Characteristics

of Groups

Customs, lifestyles, values, attitudes, aesthetics, language, education,

religion, formal and informal rules, social organization, and material objects

of each group

Historical association

Past contact and interactions between racial-ethnic groups (i.e., voluntary or

involuntary immigration, colonialism, segregation, etc.)

This material (Table 1) developed from concepts introduced by John E. Farley (2010) in Minority-Minority Relations

(6

th

ed.) published by Prentice-Hall.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 12

People may occupy multiple statuses in a society. At birth, people are ascribed status in

alignment to their physical and mental features, race, and gender. In some societies, people

may earn or achieve status from their talents, efforts, or accomplishments (Griffiths et al.,

2015). Obtaining higher education or being an artistic prodigy often corresponds to high status.

For example, a college degree awarded from an “Ivy League” university social weighs higher

status than a degree from a public state college. Just as talented artists, musicians, and athletes

receive honors, privileges, and celebrity status.

In addition, the social, political hierarchy of a society or region designates social status.

Consider the social labels within class, race, ethnicity, gender, education, profession, age, and

family. Labels defining a person’s characteristics serve as their position within the larger group.

People in a majority or dominant group have higher status (e.g., rich, White, male, physician,

etc.) than those of the minority or subordinate group (e.g., poor, Black, female, housekeeper,

etc.). Overall, the location of a person on the social strata influences their social power and

participation (Griswold, 2013). Individuals with inferior power have limitations to social and

physical resources including lack of authority, influence over others, formidable networks,

capital, and money.

Minority groups are defined as people who receive

unequal treatment and discrimination based on social

categories such as age, gender, sexuality, race and

ethnicity, religious beliefs, or socio-economic class.

Minority groups are not necessarily numerical minorities

(Griffith et al., 2015). For example, a large group of

people may be a minority group because they lack social

power. The physical and cultural traits of minority

groups “are held in low esteem by the dominant or

majority group which treats them unfairly” (Henslin,

2011, p. 217). The dominant group has higher power

and status in society and receives greater privileges. As a result, the dominant group uses its

position to discriminate against those that are different. The dominant group in the United

States is represented by White, middle-class, Protestant people of northern European descent

(Doane, 2005). Minority groups can garner power by expanding political boundaries or through

expanded migration though both efforts do not occur with ease and require societal support

from both minority and dominant group members. The loss of power among dominant groups

threatens not only their authority over other groups but also the privileges and way of life

established by this majority.

People sometimes engage in status shifting to garner acceptance or avoid attention. DuBois

(1903) described the act of people looking through the eyes of others to measure social place

or position as double consciousness. His research explored the history and cultural experiences

of the American slavery and the plight of Black folk in translating thinking and behavior

between racial contexts. DuBois’ research helped social scientists understand how and why

Image by Mikael Blomkvist, Pexels is licensed

under CC BY 4.0

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 13

people display one identity in certain settings and another in different ones. People must

negotiate a social situation to decide how to project their social identity and assign a label that

fits (Kottak & Kozaitis, 2012). Status shifting is evident when people move from informal to

formal contexts. Our ethnic or cultural identity and practices are very different at home than at

school, work, or church. Each setting demands different aspects of who we are and our place in

the social setting.

There are three major patterns of race and ethnic relations which influence the system of

stratification in the United States. The paternalistic, rigid competitive, and fluid competitive

intergroup relationships affect social status and life chances (Van den Berghe, 1958, 1978;

Wilson, 1973, 1978; Farley, 2010). The first paternalistic pattern is ascribed at birth, based on

racial composition, and determines one’s social status for life. Under this pattern, the roles and

status of majority and minority groups are understood and supported through a system of

“racial etiquette” with frequent contact between groups but the contact itself is unequal

(Farley, 2010). In this relationship, the minority group is dependent on the majority, and there

is no racial conflict or competition. Individuals who do not cooperate or break the norms are

severely penalized.

The second rigid competitive pattern is also ascribed at birth, based on race. However, under

this pattern majority and minority members compete in areas such as work and housing, and

racial groups are segregated. As competition threatens the majority group, discrimination

against the minority or subordinate group increases as well as intergroup conflict to instill

power and assertiveness among the majority (Farley, 2010).

Lastly, in fluid competitive race relations, majority and minority group members are ranked on

their own skills and abilities and able to pursue all in life. This pattern results in frequent

interracial contact in work and business settings though groups live separately primarily among

their own racial groups (Farley 2010). Nonetheless, most minorities have fewer resources to

start and compete with majority group members as a result of historic racism and

discrimination. The majority group dominates and controls the main systems and institutions to

APPLICATION 1.4

INTERGROUP DIALOGUE & SOCIAL CHANGE

Goal

To identify the function of intergroup dialogue in justice, equity, diversity, and inclusion.

Instructions

1. Read the following article:

Ford, K. A., & Lipkin, H. J. (2019). Intergroup dialogue facilitators as agents for change. New Directions for

Student Leadership, 2019(163), 47-56.

2. Explain how intergroup dialogue promotes communication and understanding about and across social

categories such as race, ethnicity, gender, and other social group distinctions.

3. Describe the ways intergroup dialogue can improve interracial interactions, relations, and social justice.

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 14

serve their own interests (Farley, 2010). In addition, competition and racial group conflicts

increase when fewer resources such as jobs are available. Even when members of a minority

group attain high status, racial stratification remains present within and outside the

subordinate group.

According to Noel (1968), ethnocentrism, competition, and unequal power lead to racial-ethnic

stratification. Ethnocentrism evaluates people and their culture from the perspective of one’s

own cultural life. People tend to believe their life and way of living is the norm and judge others

from that perspective. This attitude and mindset lend itself to categorizing people or assigning

status based on the closeness and comfort to one’s own culture. The opportunity to exploit a

group by another in competition over resources further creates a framework for social

inequality. A competitive environment or atmosphere provides the opportunity for one group

to benefit from the subordination of another (Farley, 2010). When a group is powerful enough

to dominate or subordinate others, inequality further develops. A social structure of unequal

power allows the control of one group over another solidifying racial-ethnic stratification.

The natural propensity of human behavior is to focus on self and those around us (Paul & Elder,

2005). However, people do not always value others as they value self. Without guidance and

support to appreciate and respect all humans, people lose concern for others. For example, a

stratified society fortifies an egocentric ideology to win or survive at any cost. In the plight to

obtain wealth or achieve success (i.e., education, health, resources, or money, etc.), people

strategize and fight for an advantage. This thinking legitimizes prejudice, self-justification, and

self-deception driven by ideas such as “I’m right,” “I need to earn a living,” “I work hard,” “I

deserve it,” “I’m not hurting anyone,” “they don’t matter,” or “they don’t deserve it,” “they’re

worthless,” and “they don’t belong here.”

A person’s reasoning or problem-solving skills is only as strong as their experience with an

issue, topic, or situation. Life experience plays a significant role in the ability to critically think

about issues of race and ethnicity. If you have limited experiences, your thought processes will

be limited. If you are unaware or have limited knowledge about race, ethnicity, and the social

world, then much of your thinking will have a focus on self or ego which lends itself to

egocentric, ethnocentric, and sociocentric attitudes and behaviors.

Assessing other people and our surroundings is necessary for interpreting and interacting in the

social world. When we think of only ourselves, without regard for the feelings and desires of

others, we are egocentric or self-centered. The inability to understand another person’s view or

opinion may be different than your own is egocentric. This cognitive bias is inflated when we

judge others using our own cultural standards.

The practice of judging others through our own cultural lens is called ethnocentrism. This

practice is a cultural universal meaning the behavior is common to all known human cultures

throughout the world. People everywhere think their culture is true, moral, proper, and right

(Kottak & Kozaitis, 2012). By its very definition, ethnocentrism creates division and conflict

between social groups whereby mediating differences is challenging when everyone believes

OUR LIVES: AN ETHNIC STUDIES PRIMER 15

they are culturally superior, and their culture should be the standard for living. People justify or

validate egocentric and ethnocentric thinking and behavior by reaffirming they are simply

concerned with or centered on their own social group which is sociocentrism. Overall, the ego

emphasizes self and the cultural superiority of one’s social group.

APPLICATION 1.5

SOCIAL DISTANCING BY RACE & ETHNICITY

Goal

To build knowledge of and make connections about the attitudes of people towards different racial and ethnic

groups and reflect on our own perceptions.

Instructions

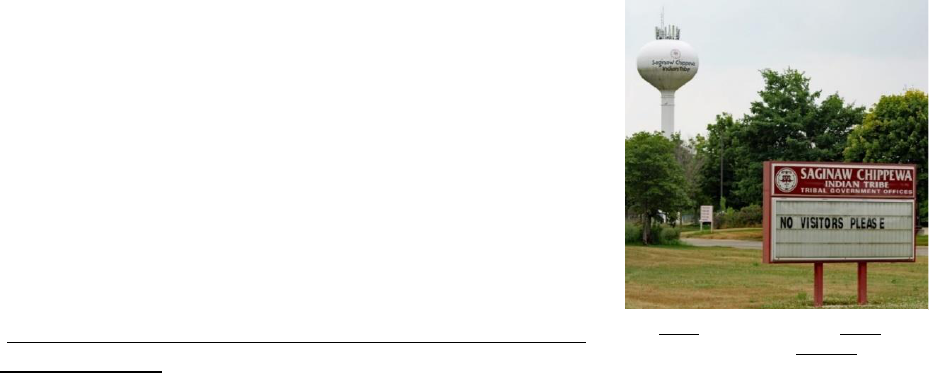

1. Study the Bogardus Social Distance Scale (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bogardus_social_distance_scale)

2. Use the scale from 1 to 7 to show how close you feel to the different racial-ethnic groups listed below.